Disclaimer: I am not a medical professional and this is not medical advice. The COVID-19 pandemic and investigations into the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine and blood clots are rapidly evolving situations. This information may be superseded by later findings. This article was last updated on March 31, 2021.

Over the past month, several European nations have halted, resumed, then once again halted their use of the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine upon several reports of serious and fatal blood clots in those who received the shot. Initial responses to these reports focused on comparing the rates of occurrence of blood clots as a broad category between populations that had received and had not received the vaccine. Blood clots, discussed generally, can refer to such conditions as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or arterial (ischemic) stroke.

Over the past month, several European nations have halted, resumed, then once again halted their use of the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine upon several reports of serious and fatal blood clots in those who received the shot. Initial responses to these reports focused on comparing the rates of occurrence of blood clots as a broad category between populations that had received and had not received the vaccine. Blood clots, discussed generally, can refer to such conditions as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or arterial (ischemic) stroke.

However, additional information soon clarified that these reports of blood clots after the AstraZeneca vaccine were not distributed among these various types of conditions in the same way that is seen to occur in the general unvaccinated population. Instead, blood clots following AstraZeneca have much more frequently been in the form of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), a blockage of the veins draining deoxygenated blood from the brain, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), in which numerous blood clots form throughout the body’s vessels. These patients were also often seen to have a paradoxical severe depletion of platelets, which produce blood clotting, similar to that seen in a rare reaction to the blood thinner heparin.

A key signal involves the rarity of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) under normal conditions: CVST is estimated to occur in only 2 to 5 out of every million people every year (Devasagayam et al., 2016). Within the German population given AstraZeneca, over the time period following vaccination, only one CVST would be expected to occur; instead, there were seven, resulting in three deaths. Frustratingly, even if a one-in-a-million condition becomes ten times more common, it may still not be common enough to appear at all in trials of merely tens of thousands of participants – so it might not be possible to detect these rare side effects before one has already administered a treatment to tens of millions.

These reports of CVST, DIC, and other unusual clotting events following AstraZeneca (now referred to as VIPIT, vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia) are still being investigated to clarify any link that may exist here, the mechanism by which this may be caused, and possible treatments. Greinacher et al. (2021), in a preprint coining the term VIPIT, claim that this is likely caused by a very small number of individuals who produce an antibody in reaction to the shot which causes activation of platelets, and assert that the condition can be treated with non-heparin blood thinners or intravenous immunoglobulin. All of this is still very preliminary and new findings may change this picture considerably. What I take issue with is the way this finding, which increasingly appears to be a real phenomenon, has been downplayed in its severity and its impacts. Greinacher and others have expressed surprising confidence in treating a condition that is not yet fully understood and has thus far been fatal in a majority of sufferers:

The scientists, who first described their findings during a 19 March press conference, recommend a way to test for and treat the disorder and say this can help ease worries about the vaccine. “We know what to do: how to diagnose it, and how to treat it,” says Greinacher, who calls the syndrome vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT).

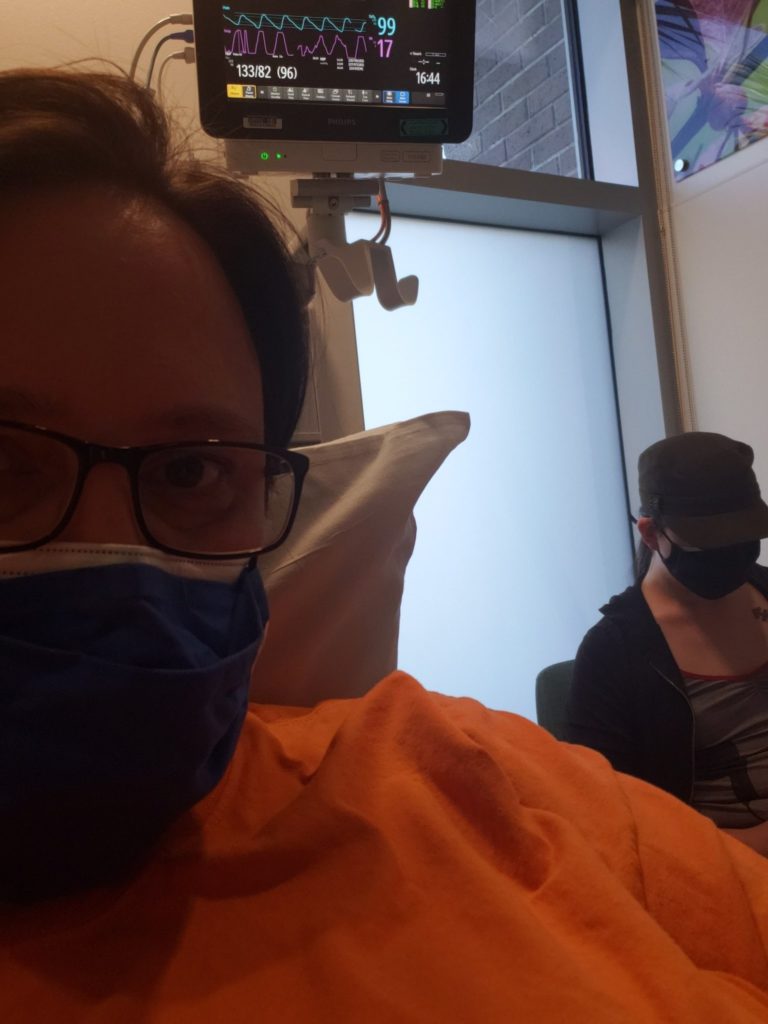

This apparent side effect has a particular resonance for me, as my wife Heather suffered from two CVSTs in June of 2020. Everything that has happened since then has made it clear that CVSTs are not easily recognized, not easily treated, not easily recovered from – and not easily survived. This is an extremely serious type of ischemic stroke that can kill you and requires urgent specialist treatment. Even in what was in many ways the best case scenario, the immediate aftermath was life-changing, as is its continued impact on Heather’s health, functioning, and mobility. As I highlight pivotal events in the course of Heather’s CVSTs and her treatment and recovery, I’d like to consider in turn how each of these key moments would be implicated in the context of a global health campaign in regions with variable access to emergency neurosurgical care.

The first thing that happened to Heather’s CVST was that nobody recognized it for a week, as her doctor misdiagnosed her severe sinus headache pain as being caused by a sinus infection and prescribed antibiotics and steroids. This made sense even if in this case it was wrong: sinus infections and sinus headaches are very common compared to a one-in-a-million condition that many doctors will not see in their entire careers, and sinus headaches aren’t considered to warrant scans that will almost always reveal nothing. A global vaccination campaign will now also be tasked with achieving a global CVST symptom awareness campaign in record time.

After a week of constant severe head pain, Heather loudly collapsed in the shower and was unresponsive and breathing erratically with her eyes fixed open and unfocused, and occasionally not taking a breath for periods of 10 to 15 seconds as her lips turned blue. I found her immediately and paramedics from the fire department down the street arrived within a few minutes to bring her to the nearest emergency room, also down the street. She regained consciousness after 20 to 30 minutes, but could not speak without the wrong words coming out, and could not speak aloud her last name or birth year; she reports that she knew the correct words in her mind but could not vocalize them properly. An initial CT scan showed a small hemorrhagic stroke on the left side of her brain, and a neurologist who was videoconferenced in from across the state via a computer on a wheel-cart assured us that she would regain her speech fully in four to six weeks. How many billion people on earth have such near-immediate access to a CT machine, or a neurologist, or telepresence technology?

Heather: He asked me my name. I replied with gibberish. He asked me my birthdate. I replied “twenty twenty twenty twenty.” I knew that was wrong when I heard it. I tried again. “TWENTY TWENTY TWENTY TWENTY!”

Heather was then given a contrast CT as well, which revealed that this was not limited to a small bleed. Instead, her cerebral sinus veins were found to be almost wholly blocked by innumerable clots. The rest of us were immediately informed that she would be airlifted to a hospital downtown, as even the 25-minute ambulance ride would not be fast enough; we were later informed that she had only a 60% chance of survival with treatment, compared to a 0% chance of survival without treatment. “Time is brain” expresses the urgency of surgically treating a stroke as soon as possible to restore normal blood flow and limit tissue damage – and every minute counts. What’s the conversion rate between Life Flights and living on less than a dollar a day?

Heather’s destination was a specialty unit for interventional neuroradiology, in which the brain is imaged during surgery while a catheter is inserted through an incision in the femoral artery and moved up into the brain’s vessels. This procedure, known as a mechanical thrombectomy, physically grabs and removes the blood clots from the vessels, re-establishing the free flow of blood. In Heather’s case, this took over nine hours, with the fluoroscopic imaging lasting so long that it produced a large rectangular patch of temporary hair loss on the back of her head.

Mechanical thrombectomy hasn’t even been in widespread use for a decade (Rennert et al., 2016); Mission Thrombectomy 2020+ reports that millions of people yearly require access to mechanical thrombectomy treatment for stroke but do not receive it, and stroke care in India, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America is hampered by substantial barriers to access such as a lack of trained professionals with the necessary equipment and infrastructure. Consider the situation of having a CVST, if it is even recognized as a CVST, in a country without this technology, and consider how that situation would in all likelihood end.

Two days after her first CVST and mechanical thrombectomy, Heather again lost the ability to speak and was found to have another CVST, requiring a second mechanical thrombectomy. We later found this likely occurred because she was taken off heparin following an allergic reaction to heparin, something her family attempted to warn staff about as she had demonstrated a severe allergy to beef; heparin is an animal product sourced from cow or pig tissues and can contain the same components that cause a reaction to beef.

On the topic of appropriate decisionmaking on heparin use in rare and complex conditions, physicians have specifically suggested not using heparin as a blood thinner in cases of suspected AstraZeneca-associated VIPIT, due to the condition’s similarity to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. In Heather’s case, she was switched to a different injectable blood thinner, then to an oral anticoagulant. How many physicians around the world will know what is happening here, and know that heparin is not suitable for this massive and widespread clotting and may actually worsen the condition? How many physicians knew this just a few weeks ago?

Heather survived her second surgery and was speaking relatively clearly that afternoon. In the weeks following her release from the hospital, she had to use a walker and needed assistance going up and down small steps. She gradually regained her fluency but has been left with a lasting sensory deficit in her right leg and foot, making it difficult for her to feel the ground and steady herself as she walks.

She suffered from severe central post-stroke pain, a central neuropathy caused by pain signals erroneously generated by the brain when it cannot properly process sensory data, which was only brought under control by a newer pain medication after several weeks. When it is not controlled, it feels like sharp impalement of the foot by a large metal pin, or grinding one’s soles on hot coals, or one’s foot being continuously boiled up to the ankle but never burning up.

To this day she experiences noticeable difficulty concentrating on tasks and recalling certain words, and she can become emotionally overwhelmed more easily. Fatigue exacerbates her neuropathic pain and sensations in her right side altogether, and sometimes even her left arm. She is on nearly a dozen medications to control her unknown clotting disorder, severe anemia, atrial fibrillation and blood pressure. She will be on blood thinners for the rest of her life, and she can no longer take any hormones due to the risk of clots. She has an appointment with at least one doctor or specialist a month, usually two, whether for hematology, gynecology, neurology, or primary care.

We have been back to the emergency room several times as a necessary precaution, even in the middle of a pandemic, when she was suspected of having another stroke or abnormal heartbeat or unexplained neurological symptoms.

We still do not know what initially caused this.

Once again, this really was something close to a best case scenario. Even with the hitches and mishaps and mistakes throughout, the extent of her recovery has been remarkable and it is something she works at with the family every day. She survived.

But this has been life-changing and harrowing, and what she’s gone through is terrible. It is necessary to understand what a CVST entails in order to understand what is at stake when we make decisions about routine use of a vaccine that may rarely cause this devastating condition.

We know the AstraZeneca vaccine works to prevent COVID-19 infection, severe disease, hospitalization, and death. We also know that COVID-19 itself can cause strokes and other serious and fatal blood clots, possibly at a much higher rate among those infected than among those given AstraZeneca. There are other considerations as well: Is an alternative vaccine available as readily and quickly as AstraZeneca without this side effect? What would be the impact of a delay in mass vaccination? Will this be found to be a matter of a minor tweak in manufacturing that could eliminate this side effect in forthcoming updates to the vaccine?

Do these risks weigh differently given the vulnerability of different demographics to COVID-19, as seen in Canada and Germany now reserving use of AstraZeneca for the elderly? (Heather, considered to be at very high risk due to her strokes and other conditions, has already received Pfizer, as have I.) Is the importance of vaccinating the global population as quickly as possible, hopefully preventing the continued circulation and emergence of new escape variants, something that overrides the possible danger posed by this side effect?

These are valid and significant questions, and they should be decided on the basis of the best available information. And when we choose to make tradeoffs, we must be clear on what it is that’s being traded. ■

2 Responses to AstraZeneca or not, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is a complex and potentially fatal emergency. Is the world prepared?