Discussions of transgender issues among the general public often take an unproductive turn when the distress of gender dysphoria is cast as something that can be remedied by simply “accepting your body as it is”. Most forgivably, this may be just the initial impression of uninformed cis people who do not want us to continue to suffer that distress, and also incorrectly believe there may be an “easier” way to reach that point without the difficulties that can be associated with transitioning. Less understandable are those who do have the time to learn and clearly know better, but instead have chosen to spend their time arguing that transitioning is axiomatically undesirable, harmful, or immoral, and therefore no beneficial outcomes could possibly justify it anyway.

Discussions of transgender issues among the general public often take an unproductive turn when the distress of gender dysphoria is cast as something that can be remedied by simply “accepting your body as it is”. Most forgivably, this may be just the initial impression of uninformed cis people who do not want us to continue to suffer that distress, and also incorrectly believe there may be an “easier” way to reach that point without the difficulties that can be associated with transitioning. Less understandable are those who do have the time to learn and clearly know better, but instead have chosen to spend their time arguing that transitioning is axiomatically undesirable, harmful, or immoral, and therefore no beneficial outcomes could possibly justify it anyway.

This intentional disregard for our own well-being, profoundly devoid of compassion or even basic agreement on the importance of the quality of a human life, is displayed in unhelpfully dismissive statements such as those from the Christian Institute:

‘I used to be trans, but I learned to love my body’…

A teenage girl who had been living as a boy has spoken out about her struggle with gender confusion and why she has now embraced reality.…

Her advice to girls who think they are boys is: “There’s nothing wrong with your body. To be straightforward, you will never be male.”

She added: “You weren’t born in the wrong body because that’s not possible.”…

But she added: “It isn’t conversion therapy to learn to love yourself, or at least, feel like you can live in your own body without hurting it on purpose.”

Sharon James of the Christian Institute later elaborated on what this concretely entails: doing nothing.

The safest approach is actually to seek to line up their child’s perception of themselves with their biological sex. There’s a natural and safe way of resolving gender confusion in young children. It’s called puberty. When children do genuinely experience discontent with their biological sex, if puberty is allowed to take its natural course, and you allow testosterone to kick in for boys, and oestrogen for girls, in the vast majority of cases gender confusion is resolved.

Other conservative Christian organizations advocating against affirmation, such as Focus on the Family, object to the very possibility of transness on the basis of certain philosophical views on the nature of the material world and human existence:

We affirm the Christian view that to be human is to be holistically united as body and spirit. Scripture teaches that even in heaven believers will have gloriously redeemed physical bodies. In contrast, transgender revisionists hold to the pagan view that the body is a container that the spirit is poured into. They erroneously conclude that either God has mistakenly put an opposite-sex spirit into the wrong body or that the body is not the real person – that only the spirit is real.

Still others attempt a secular laundering of this criticism, accusing trans advocates of advancing a philosophy of Cartesian dualism and literally claiming that a supernatural human mind exists as a separate entity from the physical human body.

It feels gratuitous, almost beside the point, to call these takes philosophically muddled – descriptive accuracy and useful theoretical clarity may not be the purpose of these belief systems. But if we may risk missing their point, they’ve made certain to miss ours. The evocative metaphor of being “in the wrong body” was intended to convey a subjective experience of the fundamental incongruence and misalignment that generally defines trans identity, spoken in the hopefully easier to understand language of a binary cis society to help others comprehend the basic fact that sense of felt gender is not always equivalent to features of sexed bodily anatomy.

This was never meant as a literal assertion that human spirit-entities exist prior to birth, that these spirits possess one of two binary gender identities, that these are at some point directed to newly developed human body, and that there is occasionally a quirk of the Gender Sorting Hat that directs a pink soul into a blue body. That would entail all sorts of further claims about the fundamental nature of the universe and consciousness that are not at all necessary in order to understand transness or recognize it as a real phenomenon whose existence is strongly established by numerous lines of consistent evidence. This phrase was the beginning of a conversation, not the end, and certainly not the meat of it. Of course criticizing one’s own willful misrepresentation of this metaphor will be easy – but it’s not a substantive reply, or even a relevant one.

More broadly, the suggestion to “love and accept your body” is entirely at odds with the clinical features of the distress of gender dysphoria. It reveals that one either does not understand or does not care what gender dysphoria even is. In the face of someone feeling this way, all this offers is: don’t. It’s like giving someone with a sinus infection a prescription for “stop sneezing”. Have you tried not being a mutant?

This is what makes these blasé recommendations so hurtful: they have no regard for the reality of trans people’s experiences of their bodies and identities, the suffering that often accompanies untreated gender dysphoria, the benefits of transition in ameliorating that suffering, or the reality that doing nothing effectively means indefinitely continuing to suffer. The pursuit of “loving and accepting” a fictional version of yourself, denying that you are trans or gender-dysphoric and instead pretending to be cis and non-dysphoric, is a state of being that many trans people are already familiar with from years of denial and repression. Yes, it has occurred to us, yes, we have tried it – it’s what we so often do before we learned to love and accept ourselves as trans. The results are already known to us. This does not end in the remission of gender dysphoria or establishing ourselves as happy cis people, only in years of preventable misery as we put off an actual effective treatment.

Whether the discussion veers toward dualism or monism of the human mind, a fully material or supernatural universe, loving and accepting one’s body or transitioning, all of these are distractions and false dilemmas when it comes to the subject of trans identities and affirming treatments. There is no need to conceive of the transgender mind and body as being separate things that are in conflict, or of cis identities and cis bodies as the only ones that can be accepted. Accepting yourself can mean accepting that you are a body with gender dysphoria and that this is a distinct personal feature you possess. For a dysphoric trans person, a cis body without gender dysphoria is indeed a fictional version of yourself – it is someone who is not you, someone who does not exist. Aspiring to such a thing is the very opposite of accepting yourself. And loving yourself can mean loving yourself enough to know and understand who and what you are even when this is difficult or intimidating, pursuing what will genuinely help you and meaningfully improve your experience of life.

The physical integration of the brain as part of the larger human body is not something that trans people were ever seeking to dispute. And unlike the assorted fumblings of various branches of theology and philosophy and poorly targeted self-help affirmations, fully physical body-mind integration does provide a useful theoretical basis on which science and medicine can function and find real, working answers. Ideally, how would you want to feel as a result of loving and accepting yourself? Consider this, just for the moment, solely from the perspective of one’s “self”, putting aside anything to do with the body one way or the other. For trans people appropriately diagnosed with gender dysphoria, medical transition treatment is associated with substantial reductions in depressive and anxious symptoms, stress levels, dissociative symptoms, substance abuse, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts and actions, and improvements in overall life functioning, sense of well-being and quality of life. These remarkable changes are not at odds with loving yourself. Loving yourself can look like this.

And what of the body, as we seek to love and accept it? What does it look like first not to accept your body, and then to reach acceptance of it? Transgender adults who have received gender-affirming medical treatment such as hormone therapy and surgery experience greater satisfaction with their bodies than trans adults who have not received these treatments (Staples et al., 2019), and consistent with the ongoing and cumulative changes induced by HRT, body satisfaction continues to increase along with time spent transitioning. Owen-Smith et al. (2018) similarly found an association between greater extent of gender-affirming treatments received and greater body image satisfaction in trans adults. A recent study indicates that this improvement in body satisfaction associated with transitioning may be experienced by trans male and transmasculine adolescents (assigned female at birth) as well.

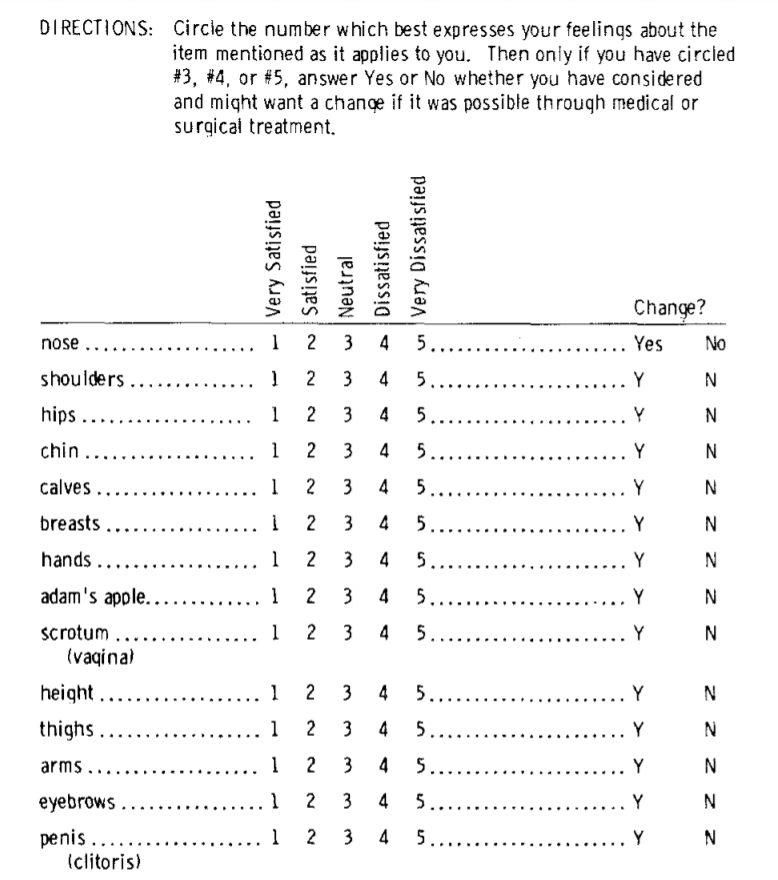

Grannis et al. (2021) studied a group of 47 transmasculine adolescents, 22 of whom had been receiving testosterone treatment for an average of 13 months. Compared to those not on testosterone, this group experienced a significant lower score (indicating improved symptoms) on the Body Image Scale (BIS), a measure of body image dissatisfaction. The BIS (Lindgren & Pauly, 1975) is essentially exactly what it says on the tin, a measure of positive or negative sentiment toward numerous specific body parts, many of them sexually divergent characteristics:

In the present study, dissatisfaction with body image was associated with depression: greater body satisfaction was accompanied by lower depressive symptoms. Love and acceptance for yourself and your body looks like this. Moreover, this study looked at patterns of brain activity in connection to anxiety symptoms. Generalized anxiety was significantly reduced among those on testosterone compared to those who were not, and this reduction was found to be associated with greater coupling between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, potentially indicating greater executive control over strong emotions such as fear.

This is what it looks like when body, brain, mind, feelings, transness, and transition are all working together as one – and all pulling in the same direction toward self-love and self-acceptance. Studies like these provide information on exactly what happens when transition treatment for trans adolescents is withheld: the only thing being affirmed is continuing depression, anxiety, and poor body image. This is what blithe cis-centric platitudes of self-love have to offer trans people: self-hate. This is all that anti-trans theologians and philosophers have for us: walls of text on how God or Daniel Dennett will be very disappointed if we don’t acquiesce to an unbearable life. This is what Sharon James of the Christian Institute considers resolution: the needless persistence of readily preventable suffering of the body, the brain, the mind, the whole transgender person.

A trans person doesn’t need to study the endless arcane speculation of hateful belief systems to know the difference between hurting and not hurting. That reality scarcely needs words at all. It’s present in our every waking moment, it lives in the very substance of our selves – we’ve even seen it in all its physicality. Loving and accepting trans bodies is the right choice for us. It’s the right choice for everyone else, too. ■