Suppose I were to show you some pictures from when I transitioned, and asked you to arrange them from start to finish, in the order you think they were taken in.

But that would be a trick question – they already are.

Contrast that with how someone on Tumblr recently described me:

“…if you watch videos of Zinnia from five years ago and ones from last week, the only difference is that Zinnia has longer hair now and wears lipstick more frequently.”

There’s an obvious disconnect between this perception and the reality. So, what exactly is going on here?

Hyper-feminine stereotypes of trans women

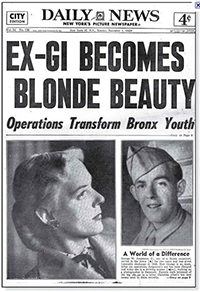

When it comes to transitioning, many people seem to equate living as a woman with being stereotypically feminine. It’s a common assumption that trans women express their womanhood via conventional or even excessive femininity. Movies and TV shows often depict trans characters as far more feminine than most cis women – at times absurdly so. Tabloids focus on conventionally attractive models and actresses; when Christine Jorgensen became one of the first widely known trans women in 1952, front-page headlines described her as a “blonde beauty”.

When it comes to transitioning, many people seem to equate living as a woman with being stereotypically feminine. It’s a common assumption that trans women express their womanhood via conventional or even excessive femininity. Movies and TV shows often depict trans characters as far more feminine than most cis women – at times absurdly so. Tabloids focus on conventionally attractive models and actresses; when Christine Jorgensen became one of the first widely known trans women in 1952, front-page headlines described her as a “blonde beauty”.

Many scholars and commentators have simply parroted these assumptions, using them to criticize the process of transition and even trans people themselves. In 2004, columnist Julie Bindel claimed that trans people are “stereotypical in their appearance – fuck-me shoes and birds’-nest hair for the boys; beards, muscles and tattoos for the girls.” And Germaine Greer described trans women as “people who think they are women, have women’s names, and feminine clothes and lots of eyeshadow, who seem to us to be some kind of ghastly parody”.

Many scholars and commentators have simply parroted these assumptions, using them to criticize the process of transition and even trans people themselves. In 2004, columnist Julie Bindel claimed that trans people are “stereotypical in their appearance – fuck-me shoes and birds’-nest hair for the boys; beards, muscles and tattoos for the girls.” And Germaine Greer described trans women as “people who think they are women, have women’s names, and feminine clothes and lots of eyeshadow, who seem to us to be some kind of ghastly parody”.

As they see it, if trans women all express traditional femininity, then this essentially implies that to be a woman is to be inherently feminine – a notion which many of them understandably disagree with. Janice Raymond, author of The Transsexual Empire, questioned whether trans women “encourage a sexist society whose continued existence depends upon the perpetuation of these roles and stereotypes” (p. 182). And Sheila Jeffreys states:

“The idea of GID is a living fossil – that is, an idea from the time when there was considered to be a correct behaviour for particular body types. Those with penises were supposed to play with particular toys and show “masculinity” such as desires to play aggressive team games and show little emotion. Those with vaginas were supposed to show “femininity” such as desires to be self-denying, do unpaid housework and wear high-heeled shoes.”

These critics conceive of transition as a kind of Sorting Hat for gender: since society often disapproves of men being feminine and women being masculine, transitioning functions to ensure that all feminine people are women and all masculine people are men.

These critics conceive of transition as a kind of Sorting Hat for gender: since society often disapproves of men being feminine and women being masculine, transitioning functions to ensure that all feminine people are women and all masculine people are men.

But all of this still rests on the assumption that trans women are universally feminine. Why would that be the case? Gender and gender expression are not the same thing, and womanhood isn’t synonymous with femininity. Most people know better than to assume that cis women all present themselves like housewives from a 1950s sitcom. Are trans women all that different? How stereotypical are we, anyway?

Measures of gender stereotypes among trans people

As it turns out, there’s a test designed to measure just that. The Bem Sex-Role Inventory lists 60 different personality traits, and asks respondents to rate how accurately each trait describes them. Some traits are stereotypically masculine, some are stereotypically feminine, and some are gender-neutral. Respondents are recorded as masculine, feminine, androgynous, or undifferentiated based on whether they show higher masculinity, higher femininity, high levels of both, or low levels of both.

Because this is a measure of gender stereotypes and not gender itself, cis people don’t all fall into either masculinity or femininity. While cis men may be classified as masculine more frequently than cis women, cis people in aggregate tend to be spread across these categories. So how do trans people compare?

A 2002 study in Poland used a derivative of the Bem Sex-Role Inventory to evaluate 132 trans people and 438 cis people. Among the cis men, 4% were classified as feminine, 48% as masculine, 24% as androgynous, and 24% as undifferentiated. In comparison, trans men were more likely to be rated feminine, less likely to be masculine, and more likely to be androgynous. These results don’t really align with the suggestion that trans men exhibit stereotypical or excessive masculinity. And among cis women, 34% were rated feminine, 16% masculine, 28% androgynous, and 22% undifferentiated. While no trans women were classified as masculine, only 52% were rated feminine, with the remainder being androgynous or undifferentiated. Trans women were actually more likely to be rated androgynous than cis women.

A 2012 study in Spain used the inventory to examine 156 cis people and 121 trans people, with somewhat different results. Here, trans women were less likely to be rated feminine than cis women, and more likely to be rated androgynous and undifferentiated. Trans men were, again, more likely than cis men to be classified as feminine, and less likely to be masculine.

Neither of these studies supports the idea that trans people are any more extremely masculine or feminine than cis people. Instead, we see that trans people express their gender in diverse ways, much as cis people do.

Historical criteria for diagnosing gender dysphoria

So, what accounts for these stereotypes? Where do people get the idea that trans women are, as Suzanne Vega sang, “more girl than girls are”? To understand this, it’s necessary to look at the history of how gender dysphoria is defined and diagnosed.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, the medical community finally began to recognize gender dysphoria as a treatable condition. They now faced the questions of how to determine if a person is trans, and whether transition treatments are appropriate for them. At a time when the very idea of medical transition was widely unfamiliar to the public, therapists and doctors aimed to make the process seem legitimate and unchallenging to social norms.

To defang the idea as much as possible, they established stringent criteria for who could transition, which sharply limited the number of people who received treatment. In 1964, UCSF announced that their doctors had performed only three transition-related surgeries in the past decade (Joanne Meyerowitz, How Sex Changed, p. 217). When the Gender Identity Clinic at Johns Hopkins opened in 1966 and began to perform operations, doctors planned on merely examining just two potential patients a month, with no guarantee of whether they would receive treatment. Psychiatrist Robert Stoller privately noted that the hospital would provide surgery to almost no one, and that thousands of people would be turned away (p. 221).

While the criteria of the clinics were supposedly in place to minimize the chances of regret among patients, and to shield doctors from legal action, they also served another purpose: ensuring that any trans people who were accepted would conform closely to gender stereotypes. In a 1973 paper, Dr. Norman Fisk of the Stanford gender clinic listed certain factors pertaining to “the overall team decision as to acceptability for sex conversion”. Among these were “appreciation of core gender principles” and “physical passability” – the degree to which a trans woman was perceived as indistinguishable from a cis woman.

So what exactly were those “core gender principles”? A 1971 paper by Stoller contains a lengthy description of what he believed to be the defining features of trans women and trans men. As children, trans women are depicted as “developing a feminine gracefulness of movement”, drawing “beautiful women”, identifying with feminine women in television or movies, and enjoying “trying on jewelry and makeup”. In adolescence and adulthood, he describes them as “avoiding masturbation” and “avoiding intercourse with females”, and expects them to have no history of marriage to women or of having children. Instead, he states that trans women will have a relationship with a heterosexual man, and, when possible, get married. Altogether, he describes them as having a “lifelong identification with femininity and feminine roles”.

Stoller conceives of trans men as equally stereotypical, stating that as children, they are “already walking, talking, and fantasying [themselves] as male” and identifying with their father’s “masculine interests”. These are said to include hunting, fishing, playing sports, carpentry, farming, and “whatever activities already reflect father’s masculine role”. He describes adult trans men as “exclusively heterosexual”, with their ideal partner being “a woman whose past history seems unfailingly heterosexual”.

Finally, he explains the clinical relevance of these descriptions:

“Only those rare patients who fulfill the criteria described above – the most feminine of males and the most masculine of females – should undergo sex transformation.”

A 1979 paper by psychiatrists at the Indiana University Medical Center sets forth similar norms, describing “primary (true) transsexuals” as follows:

“Cross-dressing often begins early, even in preschool years.” “They feel literally trapped in the wrong body… They abhor their genitals… They get no pleasure from their genitals. They are generally not interested in erotic pleasure… There is little or no active sex life with members of either sex.”

This group is contrasted with “secondary transsexuals”, who are said to be lacking a “very early onset”, while “Sexuality and the capacity to enjoy their genitals is present at some time in their history.” The authors state that their clinic’s policy considers only “primary transsexuals” as eligible for genital surgery.

Other doctors were somewhat more blunt. A 1982 paper quoted one surgeon as saying that his diagnostic process was to bully his patients, with trans women being judged as genuine if they cried. Another doctor stated that they were no longer accepting Puerto Ricans as a whole, because “they don’t look like transsexuals. They look like fags.” Gender: An Ethnomethodological Approach by Kessler and McKenna cites the opinions of two other practitioners:

“A clinician during a panel session on transsexualism at the 1974 meeting of the American Psychological Association said that he was more convinced of the femaleness of a male-to-female transsexual if she was particularly beautiful and was capable of evoking in him those feelings that beautiful women generally do. Another clinician told us that he uses his own sexual interest as a criterion for whether a transsexual is really the gender she/he claims.” (p. 118)

Even the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders incorporates gender stereotypes in its descriptions of trans people. In the fourth edition’s diagnosis of gender identity disorder, young trans women are said to have “a marked preoccupation with traditionally feminine activities”, and “particularly enjoy playing house, drawing pictures of beautiful girls and princesses…”. The text further adds that “Stereotypical female-type dolls, such as Barbie, are often their favorite toys…” “They avoid rough-and-tumble play and competitive sports and have little interest in cars and trucks”. As adolescents, behaviors such as “shaving legs” are considered to suggest “significant cross-gender identification”. Meanwhile, young trans men are said to “prefer boys’ clothing and short hair”, and “Their fantasy heroes are most often powerful male figures, such as Batman or Superman.” The fifth edition of the DSM, released in 2013, repeats many of these descriptions under the diagnosis of gender dysphoria.

The “transsexual narrative”

Trans people had a powerful incentive to meet these clinical standards: their ability to transition was at stake. The problem, of course, was that these criteria were based on archaic gender norms. Women were expected to be feminine, conventionally attractive, interested in jewelry, straight, emotional, lacking sexual interest, and married to men. Men were expected to be masculine, interested in sports and construction, and take straight women as partners. Dr. Fisk actually stated that the Stanford program offered “grooming clinics where role-appropriate behaviors are taught, explained and practiced”.

In short, these clinics seemingly aimed to produce only people who were as stereotypical in their gender as possible, perhaps not realizing that cis women may also be tomboyish, sexually outgoing, or attracted to women. There is evidence that this kind of selection process is still occurring: a 2004 study of 325 trans people seeking treatment in the Netherlands found that patients were more likely to be referred for hormone therapy when their appearance was perceived to align more closely with their gender.

So, when trans people were forced to follow these strict standards or else be denied treatment, how did they cope with this? Well, what would you do if your very gender were at the mercy of doctors who expected you to be as conforming and stereotypical as possible? Trans people learned to work the system, leading to the emergence of the so-called transsexual narrative. Not a transsexual narrative – the transsexual narrative.

When trans people were rejected from these clinics, they didn’t always walk away or give up. They would often share what they had learned about these standards with other trans people, or even read the published literature on these treatment protocols. In this way, trans people figured out how to adapt their presentation to fit what was expected of them. They crafted a narrative that matched the standards: a life story in which they were inherently feminine or masculine, exclusively heterosexual, “trapped in the wrong body”, distressed by their genitals, and aware of their gender from an early age. As early as 1968, doctors at Johns Hopkins realized what was going on, and stated:

“In data from interviews a high degree of patient motivation to obtain surgery is noted. Patients tend to skew memory and report only those feelings of belonging to the opposite gender. Most transsexual patients describe previous psychiatric experience as anxiety-provoking. Throughout the interview the patient’s strong desire to be accepted in the acquired gender role and the prospect of secondary gain may be expected to strongly influence the response to questions.”

Robert Stoller noted that “those of us faced with the task of diagnosing transsexualism have an additional burden these days, for most patients requesting ‘sex change’ are in complete command of the literature and know the answers before the questions are asked“. Dr. Fisk likewise wrote:

“…virtually all patients who initially presented for screening provided us with a totally pat psychobiography which seemed almost to be well rehearsed or prepared… it was apparent that this group of patients were so intent upon obtaining sex conversion operations that they had availed themselves of the germane literature and had successfully prepared themselves to pass initial screening.”

And in 1987, Dr. Richard Green explained:

“…few preoperative patients report any ambivalence to psychiatrists about their ‘proper’ gender or about any of their conventional sex-typed behaviors beginning with childhood. Nor do they report events from their life history that do not fit the well-publicized autobiographies of ‘successful’ transsexuals.” (The “Sissy Boy Syndrome” and the Development of Homosexuality, p. 8)

Trans people themselves acknowledge doing this. In 1987, Sandy Stone wrote:

“…the reason the candidates’ behavioral profiles matched Benjamin’s so well was that the candidates, too, had read Benjamin’s book, which was passed from hand to hand within the transsexual community, and they were only too happy to provide the behavior that led to acceptance for surgery.”

And in the 1988 book In Search of Eve, a researcher spoke with 16 trans women, one of whom said:

“What right do you have to determine whether I live or die? Ultimately the person you have to answer to is yourself and I think I’m too important to leave my fate up to anyone else. I’ll lie my ass off to get what I have to . . . [surgery].” (p. 65)

Another stated: “You must conform to a doctor’s idea of a woman, not necessarily yours” (p. 108). Other women reported telling their friends about which therapists were friendly to trans people and would allow them to access treatment quickly and easily (pp. 65-66).

I’ve actually done this myself. Where possible, I’ve referred other trans people to doctors who are known to be accepting, and otherwise, I’ve told them about the traditional stereotypes that therapists might still expect to hear. For several people I know personally, this information seemed to streamline the process of transitioning. Trans people all over the internet compare notes on their experiences at various clinics, simply to help each other out.

Because the treatment criteria so often required conformity with traditional gender norms, generations of trans women were forced to pretend to be far more feminine than they’re comfortable with. And what do we get for it? We get commentators and critics attacking us for being too feminine. In the same year that Janice Raymond complained we’re encouraging a sexist society by perpetuating roles and stereotypes, doctors at Indiana University were demanding we embody sexist roles and stereotypes. 30 years after members of the American Psychological Association admitted they judge our eligibility for treatment based on their own sexual interest, Julie Bindel mocked us for wearing “fuck-me shoes”.

Cis people set these stereotypical standards. We conformed to them against our own inclinations. And cis people now have an entrenched stereotype of us as overly feminine. Well, whose fault is that?

Negotiating trans stereotypes in everyday life

To some extent, a similar dynamic is at play in society at large. Before I started medically transitioning, my gender felt fragile – it was as if the slightest crack in my presentation would make people see me as a man. I paid inordinate attention to my hair, makeup, voice, clothes, and anything else I felt was relevant. I was extremely anxious about it, and this was stressful to those around me. Crucially, I wasn’t doing this to satisfy my own sense of how I should look – this wasn’t driven by any personal discomfort with my appearance. I was doing it to satisfy what I believed was other people’s sense of how I should look. But in doing so, I was uncomfortable: I had to present myself as more feminine than I actually wanted. Women interviewed in the 2005 paper “Transsexuals’ Embodiment of Womanhood” reported a similar phenomenon: “the initial retraining of their bodies intensified self-monitoring and feelings of inauthenticity”.

For us, certain aspects of gender presentation are more complicated than they would be for most cis women. We may wish to choose not to shave our legs or not to do our makeup; however, these choices carry the risk of being perceived, not as a slightly un-feminine woman, but simply as a man. To be seen as women, we may find ourselves having to embrace some of those archaic stereotypes of femininity – even when we don’t want to. It’s a difficult double-bind. As one trans woman in the 2005 study said:

“…I’ve always kind of rejected things that oppress women; you know, the way women are traditionally treated in society. A lot of this clothing and makeup are things that I’ve always thought were ridiculous. … I’m wondering if I do have to start wearing a lot of makeup and dressing in more traditionally feminine ways and try to get people to think of me as female.”

Many people evidently see transitioning as an acquiescence to this trap, a choice to embrace and embody these stereotypes. In reality, transitioning can actually serve as a way out. Kessler and McKenna present a study of various bodily gender cues and how people perceive certain mixed combinations of them, something which is obviously relevant to trans people. It was found that the only reliable sign that a figure was female was simply the absence of male-designated gender cues (p. 150). Several female-designated cues were necessary to ensure that a figure would be perceived as female nearly all of the time (pp. 151-152).

For trans women, transitioning tends to involve a reduction in attributes perceived as male, and an increase in attributes perceived as female. On our own, we can grow our hair out, change the way we dress, and practice altering our voice and how we walk. Medical treatment can change our facial appearance, give us a more feminine body shape, reduce our body hair, and enhance our breast growth. If the Kessler and McKenna study on gender cues is applicable to everyday life, this suggests a newfound abundance of female cues could mean we don’t have to pay as much attention to maintaining all of them. Once many of them are solidly in place, it might start to feel less like we have to push our gender cues to the maximum.

In my experience, the difference has been substantial. Before, I felt like I was walking a tightrope, constantly making sure my presentation was in perfect balance to avoid being misgendered. But after two years of transitioning, I’ve realized that I just don’t care – and now, neither does anyone else. Nowadays, makeup is a rare indulgence. I’ve shaved half my hair off because I just felt like it. I don’t need padded bras anymore, and I don’t usually bother with bras at all. I have a huge trans tattoo on my chest. For me, transitioning didn’t mean turning into Bree from Transamerica – I’m more like some kind of frumpy dubstep housewife. That’s because my gender is finally for me, not for everyone else.

The 2005 study on embodiment and womanhood lends support to the idea of this increasing comfort in our genders as we continue transitioning. The authors write: “As interviewees practiced at home, in the car, at support group meetings, and at public outings, their newly adopted voices and body movements became a taken-for-granted aspect of their practical consciousness.” They further added: “interviewees’ transformation of secondary sex characteristics increased feelings of authenticity…. Growing breasts brought forth unprecedented feelings of authenticity as women.” As one participant stated: “I can see the woman. She’s there. It’s not pretend.”

This is the key point that so many people miss: It’s not about playing with Barbies and being sexy and settling down with a husband. It’s just about being a woman. It’s not about dresses and makeup and spending hours getting ready to go out. It’s about being able to roll out of bed and stagger to the grocery store in your pajamas. It’s not something I put on in the morning anymore – it’s just who I am.

Transitioning made my gender feel less pretend and more real than ever. It gives us the breathing room we need: safer and more comfortable access to the same vast array of gender expressions exhibited by cis people. Transitioning doesn’t mean we’re stereotypical – we’re just typical. ■

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Billings, D. B., & Urban, T. (1982). The socio-medical construction of transsexualism: an interpretation and critique. Social Problems, 29(3), 266–282.

- Block, S. R., & Fisher, W. P. (1979). Problems in the evaluation of persons who request sex-change surgery. Clinical Social Work Journal, 7(2), 115–122.

- Bolin, A. (1988). In search of Eve: Transsexual rites of passage. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Fisk, N. M. (1974). Editorial: Gender dysphoria syndrome—the conceptualization that liberalizes indications for total gender reorientation and implies a broadly based multi-dimensional rehabilitative regimen. The Western Journal of Medicine, 120(5), 386–391.

- Gómez-Gil, E., Gómez, A., Cañizares, S., Guillamón, A., Rametti, G., Esteva, I., . . . Salamero-Baró, M. (2012). Clinical utility of the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI) in the Spanish transsexual and nontranssexual population. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94(3), 304–309.

- Green, R. (1987). The “sissy boy syndrome” and the development of homosexuality. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hausman, B. L. (2006). Body, technology, and gender in transsexual autobiographies. In S. Stryker & S. Whittle (Eds.), The Transgender Studies Reader (pp. 335–361). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Herman-Jeglińska, A., Grabowska, A., & Dulko, S. (2002). Masculinity, femininity, and transsexualism. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31(6), 527–534.

- Kessler, S. J., & McKenna, W. (1978). Gender: An ethnomethodological approach. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

- Knorr, N. J., Wolf, S. R., & Meyer, E. (1968). The transsexual’s request for surgery. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 147(5), 517–524.

- Meyerowitz, J. J. (2002). How sex changed: A history of transsexuality in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Raymond, J. G. (1979). The transsexual empire: The making of the she-male. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Schrock, D., Reid, L., & Boyd, E. M. (2005). Transsexuals’ embodiment of womanhood. Gender & Society, 19(3), 317–335.

- Smith, Y. L. S., van Goozen, S. H. M., Kuiper, A. J., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2005). Sex reassignment: outcomes and predictors of treatment for adolescent and adult transsexuals. Psychological Medicine, 35, 89–99.

- Stoller, R. J. (1971). Transsexualism and transvestism. Psychiatric Annals, 1(4), 60–69.

Pingback: Alice Dreger, autogynephilia, and the misrepresentation of trans sexualities (Book review: Galileo’s Middle Finger) | Gender Analysis

Pingback: Second response and follow-up questions – Omphaloskeptomai

Pingback: Gender Analysis: Zinnia Argues With People | Gender Analysis

Pingback: Identifying with a gender vs. reaffirming gender stereotypes | Gender Analysis

Pingback: “Rapid onset gender dysphoria” study misunderstands trans depersonalization, ends up blaming Zinnia Jones | Gender Analysis