Previously:

Introduction: Symptoms of depersonalization

Depersonalization is a cluster of mental and emotional symptoms generally described as feelings of unreality, with sensations that the world and one’s self are flat, lifeless, distanced, or emotionally dead (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Sufferers report experiences such as feeling that they “have no self”. They “don’t feel” their emotions; they often feel split into two parts, with one participating in the outside world and the other inside observing and commenting; they may ruminate constantly with a compulsive inner dialogue of self-scrutiny (Steinberg, Cicchetti, Buchanan, Hall, & Rounsaville, 1993). They experience a lack of agency in their own life, and can feel like a “robot” or “zombie”; they feel as if they are simply going through the motions or acting out a script. They may have obsessive thoughts over the nature of existence and reality (APA, 2013).

Depersonalization is a cluster of mental and emotional symptoms generally described as feelings of unreality, with sensations that the world and one’s self are flat, lifeless, distanced, or emotionally dead (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Sufferers report experiences such as feeling that they “have no self”. They “don’t feel” their emotions; they often feel split into two parts, with one participating in the outside world and the other inside observing and commenting; they may ruminate constantly with a compulsive inner dialogue of self-scrutiny (Steinberg, Cicchetti, Buchanan, Hall, & Rounsaville, 1993). They experience a lack of agency in their own life, and can feel like a “robot” or “zombie”; they feel as if they are simply going through the motions or acting out a script. They may have obsessive thoughts over the nature of existence and reality (APA, 2013).

They may sense that they are almost physically separated from the world by a glass wall, veil, fog, bubble, or skin; their perception of the world becomes somehow colorless or like a picture with no depth; they experience the world as “unreal”. Their emotional numbness becomes a bodily sensation and they feel as if their head is filled with cotton. They may struggle to imagine people or places vividly (APA, 2013). They feel that they are disconnected from life; while they can still think clearly, some essential quality seems to have been lost from their experience of the world (Medford, 2012).

Although depersonalization is considered a dissociative symptom, there is notably no element of delusion or false beliefs about reality. Instead, it is the texture of conscious experience and existence itself that takes on an “unreal” feeling (Steinberg et al., 1993). Depersonalization can co-occur with depressive and anxious symptoms, but it has been established as a distinct symptom – it is not a “negligible variant” of depression or anxiety (Michal et al., 2016).

Depersonalization causes functional, social, and occupational impairment comparable to or worse than that associated with depression or anxiety. Sufferers are more likely to be unemployed, more likely to be single, and more likely to be living with their parents (Michal et al., 2016); children aged 12–18 more often report social insecurity and avoidant coping strategies, and are more likely to repeat a grade of school due to poor performance (Michal et al., 2015). Crucially, individuals with depersonalization often find the experience deeply disturbing and distressing (Medford, 2012). While it may seem paradoxical to experience both a lack of emotion as well as intense emotional pain (APA, 2013), depersonalization is nevertheless experienced as such a “painful absence of feeling”. As one woman stated: “I fully, fully thought that I’m dead, everything is completely futile . . . And if I’m not dead, then I just don’t care enough about anything to be properly applying myself to any of this.”

“I don’t have any emotions – it makes me so unhappy.” (Medford, 2012)

Worryingly, depersonalization symptoms are also associated with a greater likelihood of suicidal ideation (Michal et al., 2010). Simeon (2004) notes that “distress associated with depersonalisation disorder can be profound”:

Many people experiencing it find the robotic, detached state analogous to the ‘walking dead’, and deeply question the meaning of being alive if they do not feel alive and real.

One sufferer described his desperation: “I don’t know where the real me has gone. . . . I feel so depressed, like I can’t go on living this way but I live in hope that one day I will wake up and it will be me” (Baker et al., 2003).

There is also no established treatment for depersonalization. Clinicians have treated sufferers with SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, opioid receptor blockers (Sierra, 2008), transcranial magnetic stimulation (Jay, Sierra, Van den Eynde, Rothwell, & David, 2014), and psychotherapy such as specialized cognitive behavioral therapy (Hunter, Charlton, & David, 2017). But no one treatment has been shown to have a reliable effect on depersonalization symptoms.

Depersonalization in the context of gender dysphoria

Gender dysphoria is highly comorbid with psychiatric symptoms such as depression and anxiety, and these mental health issues tend to improve following cross-sex hormone therapy (Costa & Colizzi, 2016). Transgender people also have an elevated prevalence of dissociative symptoms, with Colizzi, Costa, & Todarello (2015) finding that 29.6% of gender dysphoria patients experienced a dissociative disorder (10.2% were reported to suffer from either depersonalization disorder or derealization, a type of depersonalization). Similarly, the intensity of depersonalization symptoms is known to decline throughout transition, particularly after starting hormone therapy. Researchers have even questioned “whether the dissociation is to be seen in this case not as an expression of a pathological dissociative experience but rather as a genuine feature of the GD” (Colizzi, Costa, & Todarello, 2015).

Depersonalization symptoms remain an underrecognized aspect of gender dysphoria, likely due in part to the lack of awareness of depersonalization among the overall population. While the prevalence of clinically significant depersonalization in the general population is known to range from 1 – 3.4%, only 0.007% of the general population has received a diagnosis (Michal et al., 2016; Michal et al., 2011); this has been described by researchers as “a dramatic neglect of DP in clinical routine” (Michal et al., 2011). Sufferers typically experience these symptoms for 7 – 12 years before being diagnosed (Hunter et al., 2017). Simeon (2004) emphasises the importance of clinical familiarity with these symptoms:

As is typical with various poorly recognised and under-treated disorders, patients can feel tremendous relief from contact with a clinician who is able to recognise their symptoms for what they are, is familiar with the basic presenting features of the disorder and is able to give this elusive condition a name and to let the patient know that he or she is not alone in this disorder. Patients frequently feel as if they are the only person experiencing this disorder, when in fact they are not.

One barrier to recognition is “the ineffable quality of the experience” of depersonalization (Sierra, 2009). Steinberg et al. (1993) note that the symptom “can sometimes go unnoticed or can be experienced by patients habituated to it as ‘normal.’” By the 1930s, researchers had remarked on the difficulties of describing the experience of depersonalization at all: “What has really been changed or diminished with the onset of depersonalization cannot be expressed in speech. Even educated people (as in some cases in the literature) have given no clearer description, they only used metaphors” (Mayer-Gross, 1935, in Sierra & David, 2011). Some sufferers use specific visual imagery to try and convey what their depersonalization feels like (Mendes de Oliveira & Fernandes de Oliveira, 2013):

Mendes de Oliveira & Fernandes de Oliveira (2013) describe a patient who compared her experience of depersonalization to the photo “Weeki Wachee Spring, Florida” by Toni Frissell (1947).

“Charlton independently came up with the image of the little man sitting in her skull, but was then amazed when she found a sketch online depicting precisely the same figure. It remains high on a Google image search for DPD.”

Trans people experiencing depersonalization can find it just as difficult to describe this disconcerting alteration in the texture of consciousness to themselves or to others, and may not even realize that anything is wrong until these sensations begin to abate. Immediately after I started hormone therapy, a trans woman and personal mentor told me: “You’re going to feel AMAZING in a month or so.” While I wasn’t sure what she meant at the time, I soon began to experience a lifting of my depersonalization. My posts and other notes from around this time often refer to clear instances of this symptom, even though I was largely unaware of depersonalization as a discrete phenomenon.

After nine days of HRT, I described myself as being “in a ridiculously good mood”, with “an ability to see [my feelings] more clearly”, and added: “The grass is the same color as it is over there – I’m just seeing it a little differently now.” Five weeks in, I noted that “I haven’t felt this calm, happy, confident, in control and well-integrated in years – if ever.” And after two months, I described the unexpected changes in my experience of emotions: “instead of either feeling totally numb or abruptly bursting into tears, I have a whole repertoire of emotions available to me now. . . . These aren’t mood swings – they’re mood symphonies. This is all unbelievably cool, and I wouldn’t have known what I was missing without experiencing it firsthand.”

However, it wasn’t until seven months into HRT that I began to explain these effects in terms closely matching depersonalization symptoms, attempting to imbue these descriptions with the very passion and vividness that had been so lacking in my life before:

Even if it had no physical effects at all, the overall improvement in mood would be completely worth it.

For my entire life before now, it always seemed like there was something subtly wrong about me. . . .

I frequently felt out of place in my own life. Sometimes, things seemed less than fully real. It was like I was just going through the motions, doing what I was expected to do. When I talked to people, it felt like I was acting, like I was reading off a script.

I could barely even feel anything. I couldn’t cry when it seemed like I should be crying – it was like being estranged from my own emotions. Or, when I rarely did manage to cry, it was so overwhelming that I would completely lose it and then, for the next day or so, my head would feel so clouded and heavy and just dead inside. . . .

Life felt pointless. Nothing was all that fun. Nothing seemed very enjoyable. . . .

I assumed that was simply my nature, and I would have to get used to it, live for a while, and then die, and that’s pretty much it. . . .

Everything – the distance from my own feelings, the alienation from my own life, the unreality of it all, the inability to cry, the dead feelings, the tension, the irritability, the pointlessness of life – everything that had been suffocating me since I was a child just melted off me and then I was actually, really ME for the first time ever in my ENTIRE LIFE.

There was really, truly a REAL PERSON in there and I never even knew it. If there were missing pieces, I got them back. I can feel everything now. . . .

Everything seems brighter and more real. Life isn’t an ordeal anymore – it’s worth living now!

I used to feel like there was some ever-present invisible skin that enveloped me and kept me from ever actually touching the world or letting the world touch me. Now I’m there. It really feels like I’m truly part of the world now.

I soon found that these experiences resonated with many other trans people, who would sometimes remark that the resemblance to their own feelings was uncanny. Many noted that they found this validating and were comforted and reassured to know that they were not alone in experiencing these symptoms. As Colombetti & Ratcliffe (2012) observe:

. . .patients often complain that an inability to understand or articulate their experience adds to its unpleasantness. Hence, as Simeon and Abugel remark, the “vast terrain of depersonalization would benefit from a broader lexicon to help find words for the unspeakable.”

In the years since I shared these experiences, countless additional trans people have described their own histories with depersonalization, as well as how transition has affected these symptoms. Clearly, the handholds offered by such firsthand narratives and detailed metaphors provide sufferers with an important opportunity to recognize similarities in their own lives, and may help them put these symptoms into context with their experiences of gender. To that end, I interviewed 11 trans people who volunteered to share their experiences of depersonalization for the benefit of the community. As you read these narratives, pay attention to the characteristic feelings of unreality reported by many participants, the specific metaphors and motifs that recur in their descriptions, and the deep distress and torment caused by these symptoms.

Trans people talk about their experiences of depersonalization

(Responses have been edited for length and clarity. Some names have been changed for privacy.)

Ada, trans woman

I’m a late life transitioner, 4.5 months in, and I struggled with depersonalisation pretty much my whole life. And it lifted when I was finally honest with myself about my identity. . . .

For me, the biggest most obvious aspect of it was a permanent sense of detachment from my emotions. Like I had the feeling that I was being prompted “This is where a normal person would feel sad” and I’d get the vaguest hint of sadness, but nothing more. It was the same with joy or pretty much any other feeling. I could fake the emotions, but I didn’t *feel* them.

I also had the sense of directing myself. Like I would decide ahead of time how I should approach a conversation, or how I should feel. I would consciously analyze the situation and give myself directions, which would then play out. This wasn’t a literal script, but felt more like a director giving an actor guidance. “Be more emotive. Talk more slowly to build empathy”, etc. Basically, it was like there was a filter between me and the world. . . . And I simply couldn’t make myself *care* about anything. I had no drive and no passion. I felt like a husk, just existing my way through life, not living it.

Lycha, trans woman

I think I was searching for a connection to the feminine, in general. When I would lose that, via a break-up, depersonalization/derealization got worse. It was like being a zombie who didn’t have a full emotional palette, at least not at the surface. Deep down, I felt. I felt things intensely, and sometimes listening to alternative rock and grunge on the radio, I would get an intense mourning sense of nostalgia… but so hard to bring that to the surface.

It was so bad around people. It was like I wasn’t myself around others. Not just like I couldn’t be myself, but almost like myself wasn’t really even there. I felt like a fake and a fraud all the time. Other people would get to know me and realize I was presenting an image. Sometimes I got called out on it. But I couldn’t figure out what was fake about my outward self.

It was as if I was continually trying to approximate who I really was, using a very limited means of expression. Like painting a rainbow with only two colors of paint, or trying to replicate an M. C. Escher drawing using a dull piece of charcoal. When I spoke with transgirls, realized I was like them, started researching, and opened my mind… I knew there were other ways of creating art that i didn’t yet have access to, like a box of 64 colors of crayons that I wanted and envied yet didn’t have the money to buy.

So there was a way to be me, but I just didn’t get there until HRT, and it was like a veil lifted. . . . The depersonalization of my dysphoria, when it came to expressing myself, was like trying to play a symphony on a piano where only two or three keys worked. I could play some sounds, and almost make a melody, but I just had no way of expressing myself in the fashion that I needed to. HRT was like someone fixing the piano keys. But it was like I just didn’t realize the piano could be fixed. It wasn’t like I went up to my parents and said, ‘Mom and Dad, the piano is broken and needs fixed.’ I didn’t realize that the other keys were even playable.

So it was like I would have symphonies in my head that I wanted to play, but I had no way of creating them. I just coasted through life banging the same few keys to make sounds, and it always felt meaningless, going nowhere. And I could tell I was empty and fake and didn’t know why. Playing the same few keys over and over, you feel like a robot instead of a pianist.

El’li, 31, trans woman

For the longest time I didn’t have the words to describe it. It took me forever to convey it to people, even if they were experiencing it. I used to refer to it as “being aware of your existence.” I knew right away that I wished it on no one and saw what it could do to someone, despite not truly experiencing the negative. . . .

… I analyzed everything. My thoughts, my actions, others around me. I had even used it to force myself awake when the alarm would go off. My mind would be on the moment I would open my eyes. . . .

I cannot say if my gender dysphoria had triggered what I had felt throughout my life or not, but it most definitely was part of the problem. Transitioning as known by many, if not all, is not the answer to everything wrong in your life, yet it was when I saw this article on depersonalization I finally knew I wasn’t imagining it disappearing. It’s been gone for around a year now. It was a gradual union in the two pieces of myself. . . . I’ve become a normal person, or at least how I view a normal person without depersonalisation. I cannot say that transitioning healed it, but I can say it made it possible for me to heal it.

Thana, nonbinary

It was a lot of fluctuating between very internalized and externalized views of reality. Sometimes it was feeling like all existence was a meaningless construction of my mind, and sometimes it was feeling like reality was happening without me and I was just an observer. I was constantly switching between feeling powerful and powerless. I obsessed over trying to understand my experiences of reality to a point where it dominated most of my thinking. Mentally it was quite draining and really scary.

It wasn’t until a friend who had similar experiences talked to me about it and that’s when I learned about depersonalization and derealization. Honestly having a label to apply to the experiences really helped me deal with them. In addition to that I was using a lot of art to deconstruct my experiences, which didn’t necessarily provide obvious answers but it was a useful form of catharsis. Creating my own world where I had complete control over what reality was, where the characters and I sort of had this mutual exchange of information really helped. The world and characters I created felt more real than anything else since they were so closely tied to me. It was like I was creating different versions of myself I could talk through these experiences with, and it gave me the opportunity to form safe spaces where I could explore my own thoughts, which I think ultimately is what I really needed.

In hindsight I look at my art and it seems pretty obvious that I was working through some degree of gender dysphoria or something similar. Lots of characters that were trans, nonbinary, androgynous, etc. Eventually I slowly realized that I was creating these versions of myself that I aspired to be but they seemed completely out of reach. Once I started to come to terms with my identity these imaginary versions of myself and my actual self started to merge and everything started to feel a lot more real and liberating. I was completely apathetic about my body before and now I actually treat it as this real, tangible thing that’s a part of me since I finally feel more like myself. I think allowing myself to acknowledge my identity helped me overcome my obsessions about reality since it gave me a freedom over my thoughts and self-expression that I didn’t think I could have. Now instead of feeling completely disconnected from reality I feel like I can participate in it.

Audrey, 33, trans woman

When I first started to experience it it was a distancing from my body. I’d come to accept that my body wasn’t a girl’s body, and that consequently it mustn’t be mine. It was a reaction, at first, I think. A way to try to make the information that wouldn’t all fit together at least work separately. I created elaborate justifications based on media I’d been exposed to as to how I was myself without my body being out of place. It was a stress. A disappointment. A reason to find new ways to conceptualize self to allow something like me to exist. Puberty complicated this. It made it impossible to intellectualize that disconnect. Over the course of five-ish years, I just let more of me go. As it progressed, I sent from feeling like a stranger in a familiar skin to understanding my body, my life, and my feelings as the properties of a machine I had very little and very subtle input into. Distancing myself from expected social norms, which happened in a very few social circles, made it feel a little less distant. Like I had to use other people as a mirror, because everything I knew about myself was always going to be wrong, but at least I could directly interact.

I thought of the experiences as normal until my mid-teens, when I spoke about it and was informed it was nothing of the sort. I grew to think of it as a way to navigate the stresses of the world. Like I’d coded a “self” routine sufficient to survive and deflect a majority of deeper inquiry and allowing internal conflict to continue without interrupting the life process. A way to survive being deeply unlike myself. All kinds of things I wouldn’t normally think or do MUST be thought or done as part of living. So they would happen almost outside me.

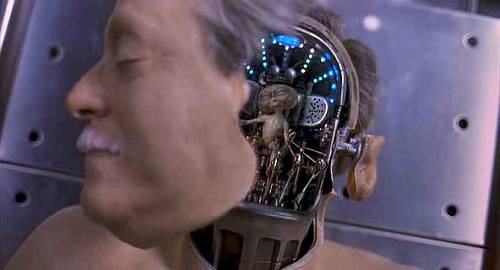

I eventually got really invested in the imagery of my body as a robot that some very primal feelings were directing. Clumsy, crude, but very present in the physical world that I didn’t appear to exist in.

Josie, 26, nonbinary trans woman/demigirl

I felt a lot like I was disconnected from my body. Like it was just empty and I was this other thing slightly outside controlling it. The excessive self scrutiny part of your article caught my eye too. I often had to put a lot of specific effort into moving and emoting and was constantly criticizing small aspects of my interactions. In essence I felt like my body was kind of a puppet or something I had to make seem real. . . .

During puberty is when these feeling manifested. Before then I was mostly unconcerned with my body and just kinda doing kid stuff. During puberty is when I started to feel detached from everything and the pain experienced when I wasn’t dissociating got more intense the older I got. During my transition (I’ve been on hormones for a year as of this past Friday), I’ve definitely experienced a sense of unity with my body. I still dissociate and stuff a lot (though there are other mental health concerns involved in that). But it’s more like I can experience natural instincts and not have to try as hard to emote and stuff like that. . . . Like I’m able to actually have mannerisms and not think super hard about executing them. I still have some social issues (kinda looking into other reasons why that might be) but not as the result of depersonalization.

Quinn, 19, trans woman

I’m a 19-year-old trans girl and I definitely felt a lot of depersonalization before I started HRT.

I have two distinct memories about these sorts of feelings. I felt very disconnected from my emotions – aside from the depression I felt, I frequently thought that I just didn’t have the kind of emotional depth that others did. I almost never cried or became giddy or really felt any emotion with that amount of intensity. Even at my most depressed, it was as if the logical part of my brain was working itself in circles about it while the emotional part registered nothing at all. That was frustrating, because it felt like I couldn’t feel or express emotions correctly. The other feeling I remember having frequently was a distinct sense that my reality as I experienced it wasn’t real in a few different ways. This was most apparent right after I watched films or TV shows and I felt like my entire life was as fictional as what I had been watching. I did a lot of recording myself as a teenager, and I felt a very similar feeling when watching or listening back to recordings of myself. For an hour or two after doing that I’d feel an intense deja vu, as if I was doing everything by a script. . . .

I wish I could answer the question of how it changed around puberty, but I just don’t remember back that far. Everything I mentioned really slowed down once I moved to college and came out there. I started HRT in January (7 months as of today!), and I want to say I’ve felt the deja vu / derealization stuff maybe two or three times since then. It did take a few months of HRT before I felt able to consistently feel emotions in appropriate amounts. I wouldn’t say these feelings and experiences entirely went away, but they seem to be less pronounced and therefore less stressing to me. I feel the slight amounts of these things I do experience anymore is more of a manageable part of my personality than something completely broken about my brain.

Haz, 18, nonbinary

For me, it’s like watching life as a spectator in a movie theatre, or reading my life in a book, there’s this sense of inevitability about everything I do, adhering to a script and a status quo – it’s very linear, and there’s numbness and falseness to it. My body feels prosthetic, the only thing I feel really in control of is my mind, but only then as a spectator or an onlooker.

Everything from taste to smell to touch to sexuality and intimacy and conversation feels manufactured and cold and empty. . . .

Oh god yeah, puberty made me feel like my face wasn’t my face, my skin not my skin, the hair that started to grow didn’t feel like my hair and rather than be ashamed of it I’d let it grow and become distant from it.

Garry, 20, transmasculine

Prior to reading your article on it (which was very validating, btw) I wondered frequently that if I was a Real Trans™ why did I not physically feel dysphoria 24/7? Upon some observation, I noticed that for the majority of my waking life I felt like my mind and body were separate entities. Like the real me, my consciousness, was trapped somewhere in my brain, and my body was at most just a proxy for interacting with the outside world. I’d never thought about it before, and I didn’t realize it wasn’t normal until I did.

Life itself felt like a dream and I wasn’t really living it. At times I got so trapped within my own mind I could barely be present when hanging out with friends, and that was super upsetting. Any time when I was sort of mentally present in any way, I either felt like a floating head or like my skin was crawling and my body was just wrong. Stuff like that.

Jennifer

For me especially when I was younger it felt like I had a completely different person inside of me. It was like there was a person on the outside, and there was who I really was hiding deep inside, and she was too scared to come out. It was always like I was looking at the world through someone else’s eyes and even though I was in control I never really cared about my body because it never felt like mine. I used to think of it as like the little space alien with the human exo suit in Men In Black. For a long time I didn’t understand why nothing felt right, like the world was just happening around me, and I was just an observer stuck watching as life happened.

Anna

It felt like I was removed from my self. Not in the sense of an out of body type of way, rather I found (past tense – I have been on HRT for around a year now and it has greatly reduced this issue) my emotions dulled, and easily discounted. Even things that I wanted to care about where very difficult to make matter to me, like filling out paper for graduation – I knew I needed it do, I wanted it done, but it didn’t seem to affect me. Additionally it caused me to discount my relationships with other people. This caused me some issue as I was prone to yield to other people whenever our preferences clashed, it wasn’t so much that I was being polite – although some took it that way – rather I just felt so disconnected with what I wanted that I couldn’t bring it to matter. Oddly enough this helped with my work, as I tended to write very objectively which my professors liked.

A metaphor for this might be that of playing a video game, while the player assumes the role of the protagonist. Knowing what that character is feeling and thinking the player can make choices for them. Yet often those emotions that the character feels are not what the player feels. In the same way while I may be aware of a feeling it often did not feel like I was experiencing that emotion myself, rather it was like I was merely aware of them.

What you need to know about gender dysphoria and depersonalization

The role of depersonalization symptoms in the lives of those with gender dysphoria is largely underrecognized, even as such narratives are surprisingly common among transgender people. The experience of depersonalization may contribute to certain psychosocial phenomena observed by those working with trans and gender-nonconforming youth: Olson & Garofolo (2014) note that at the onset of unwanted puberty, gender dysphoria may present as social isolation, declining academic and social functioning, maladaptive coping mechanisms, and suicidality, all of which are elevated among adolescent or adult sufferers of depersonalization. Symptoms of depersonalization are also noted to appear at an average age of 16 (Simeon, 2004). Similarly, researchers studying the origins and treatment of depersonalization may gain additional insight from the finding that transition, particularly cross-sex hormone therapy, reduces these symptoms.

In light of the association between gender dysphoria and depersonalization, those who are questioning their gender or whether to transition can benefit from awareness of the possibility that these feelings are an aspect of dysphoria. Because such experiences can be more nonspecific and don’t always appear to relate to obvious discomfort with one’s gender, those with these symptoms may think they aren’t really feeling dysphoria, unaware that these feelings may indeed be part of dysphoria itself (“that was dysphoria?”). Individuals considering transition should take into account the potential for these feelings of depersonalization and unreality to decline markedly.

The general public should understand that transition care is of substantial benefit to trans people’s mental health, reducing symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and depersonalization. If this is indicated for us and we are in need of this care, it is not just as well something that we can choose against in favor of some other treatment or no treatment. This is not a small thing – the change that this makes possible in our lives is invaluable. Access to this medically necessary care can mean the difference between empowering us to be our best selves, and condemning us to a state of living death. ■

Special thanks to all interviewees for sharing these important narratives.

Have you experienced depersonalization symptoms as part of gender dysphoria? Tell us about it in the comments!

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Excerpt]

- Baker, D., Hunter, E., Lawrence, E., Medford, N., Patel, M., Senior, C., . . . David, A. S. (2003). Depersonalisation disorder: clinical features of 204 cases. British Journal of Psychiatry, 182(5), 428–433. [Full text]

- Colizzi, M., Costa, R., & Todarello, O. (2015). Dissociative symptoms in individuals with gender dysphoria: is the elevated prevalence real? Psychiatry Research, 226(1), 173–180. [Abstract]

- Colombetti, G., & Ratcliffe, M. (2012). Bodily feeling in depersonalization: a phenomenological account. Emotion Review, 4(2), 145–150. [Abstract]

- Costa, R., & Colizzi, M. (2016). The effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on gender dysphoria individuals’ mental health: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 1953–1966. [Abstract] [Full text]

- Hunter, E. C. M., Charlton, J., & David, A. S. (2017). Depersonalisation and derealisation: assessment and management. BMJ, 356, j745. [Abstract]

- Jay, E.-L., Sierra, M., Van den Eynde, F., Rothwell, J. C., & David, A. S. (2014). Testing a neurobiological model of depersonalization disorder using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Stimulation, 7, 252–259. [Abstract] [Full text]

- Medford, N. (2012). Emotion and the unreal self: depersonalization disorder and de-affectualization. Emotion Review, 4(2), 139–144. [Abstract]

- Mendes de Oliveira, J. R., & Fernandes de Oliveira, M. (2013). Depicting depersonalization disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(3), 263–264. [Full text]

- Michal, M., Adler, J., Wiltink, J. Reiner, I., Tschan, R., Wölfling, K., . . . Zwerenz, R. (2016). A case series of 223 patients with depersonalization-derealization syndrome. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 203. [Full text]

- Michal, M., Duven, E., Giralt, S., Dreier, M., Müller, K. W., Adler, J., . . . Wölfling, K. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of depersonalization in students aged 12–18 years in Germany. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(6), 995–1003. [Abstract]

- Michal, M., Glaesmer, H., Zwerenz, R., Knebel, A., Wiltink, J., Brähler, E., & Beutel, M. E. (2011). Base rates for depersonalization according to the 2-item version of the Cambridge Depersonalization Scale (CDS-2) and its associations with depression/anxiety in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 128(1–2), 106–111. [Abstract]

- Michal, M., Wiltink, J., Till, Y., Wild, P. S., Münzel, T., Blankenberg, S., & Beutel, M. E. (2010). Type-D personality and depersonalization are associated with suicidal ideation in the German general population aged 35-74: results from the Gutenberg Heart Study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 125(1–3), 227–233. [Abstract]

- Olson, J., & Garofolo, R. (2014). The peripubertal gender-dysphoric child: puberty suppression and treatment paradigms. Pediatric Annals, 43(6), e132–e137. [Abstract]

- Sierra, M. (2008). Depersonalization disorder: pharmacological approaches. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 8(1), 19–26. [Abstract]

- Sierra, M. (2009). Depersonalization: A new look at a neglected syndrome. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Books]

- Sierra, M., & David, A. S. (2011). Depersonalization: a selective impairment of self-awareness. Consciousness and Cognition, 20(1), 99–108. [Abstract] [Full text]

- Simeon, D. (2004). Depersonalisation disorder: a contemporary overview. CNS Drugs, 18(6), 343–354. [Abstract] [Full text]

- Steinberg, M., Cicchetti, D., Buchanan, J., Hall, P., & Rounsaville, B. (1993). Clinical assessment of dissociative symptoms and disorders: the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D). Dissociation, 6(1), 3–15. [Abstract] [Full text]

Citation: Jones, Z. (2017, August 31). In our own words: transgender experiences of depersonalization. Gender Analysis. Retrieved from https://genderanalysis.net

Pingback: Themes of depersonalization in transgender autobiographies: Jan Morris | Gender Analysis

Pingback: I Tried Detransition and Didn’t Like It | Gender Analysis

Pingback: 5 things to know about transgender depersonalization | Gender Analysis

Pingback: What is Gender Dysphoria?

Pingback: Gender Analysis in Slate: An interview on trans depersonalization and “rapid onset gender dysphoria” | Gender Analysis

Pingback: “Rapid onset gender dysphoria” study misunderstands trans depersonalization, ends up blaming Zinnia Jones | Gender Analysis

Pingback: Progesterone may not be only beneficial or ineffective for trans women – for some, it can be actively harmful | Gender Analysis