FLDOH’s anti-trans guidance cites several sources which actually support access to gender-affirming care

Previously: The FLDOH guide to parenting: Ignore a child’s issues, and just hope it all goes away

The Florida Department of Health’s 2022 anti-trans guidance declares:

One review concludes that “hormonal treatments for transgender adolescents can achieve their intended physical effects, but evidence regarding their psychosocial and cognitive impact is generally lacking.” . . . Social gender transition should not be a treatment option for children or adolescents. Anyone under 18 should not be prescribed puberty blockers or hormone therapy.

This obnoxious formatting implies that the linked resources support these positions. That is false: most of these sources clearly contradict the FLDOH guidance and do not recommend against social transition, puberty blockers, or hormone therapy for those under 18.

Sievert et al. (2021) do not oppose social transition for children or adolescents

FLDOH cites Sievert et al. (2021) in asserting:

Social gender transition should not be a treatment option for children or adolescents.

But Sievert et al. do not support this statement at all. The sample in this study consisted of gender-dysphoric children aged 5-11, not adolescents. The authors emphasize “the importance of individual social support provided by peers and family, independent of exploring additional possibilities of gender transition during counseling” and does not take a position against social transition. Instead, the authors cite two prevailing approaches to gender dysphoria, one which recommends social transition as an option for adolescents but not children, and the other recommending social transition as an option for both:

For example, de Vries and Cohen-Kettenis (2012) recommended for young children to not yet make a complete social transition before the very early stages of puberty. In contrast to this clinical management, a more gender affirmative approach freely endorses social transitions when they are perceived as appropriate (Ehrensaft et al., 2018; Giordano, 2019).

The clinic in this study states that in their practice, they allow for the possibility of social transition for children as well as medical treatment such as puberty blockers or hormone therapy for trans adolescents:

The Hamburg GIS for Children and Adolescents at the University Medical Center Hamburg- Eppendorf was founded in 2006 (Möller et al., 2014). All treatment performed at the clinic comply to the international guidelines for the SoC 7 released by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) in 2012 by Coleman et al. (2012). Clinicians follow a diagnostic and treatment protocol that was developed and in the past referred to as the “Dutch Model” (Cohen- Kettenis et al., 2011; Delemarre-van de Waal & Cohen-Kettenis, 2006; de Vries & Cohen-Kettenis, 2012). This clinical management approach suggests a watchful-waiting approach which differentiates counseling in contrast to a more gender affirmative treatment approach during adolescence (Cohen-Kettenis et al., 2008; Edwards-Leeper, 2016; Giordano, 2019). Sessions may include clinical diagnostics, counseling, psychotherapy and psychoeducation during childhood, as well as the possibility of referral to an endocrinology specialist for medical interventions after the onset of puberty. After a comprehensive diagnostic and psychological evaluation over multiple sessions, medical interventions are currently recommended in Hamburg if GD during adolescence is persistent (without strict onset criteria) and accompanied by distress, if adolescents present the ability to consider and anticipate treatment options as well as possible consequences of a life in the preferred gender role. The psychosocial treatment modalities are based on a psychodynamic and developmental perspective and similar to a supportive watchful-waiting approach. This means that steps of social transition during childhood are supported in individual cases, when the family is open to such a step and if a child clearly expresses the desire to proceed to live in their experienced gender. Decisions are never being made by a clinician alone, but in line with current SoC7, where clinicians, children and parents identify the best individual pathway together (informed consent), and in relation to the personal social circumstances (Coleman et al., 2012). Psychotherapy offered include psychodynamic individual and family sessions with a frequency tailored to the child’s individual needs.

Sievert et al. explain that while an individual child’s status of social transition was not directly found to be predictive of improved outcomes, support from parents, family, and peers was associated with better psychological functioning in trans and gender-questioning youth:

At the same time, however, most of this previous clinical research from Europe has not explored the possible role of the social transition status for psychological functioning outcomes. Nowadays, the two main explanations for elevated vulnerability and distress within this group are the state of conflict between one’s self-understanding of one’s gender and physical appearance on the one hand (Aitken et al., 2016), and lacking social support or poor peer relations (PPR) on the other hand (Aitken et al., 2016; Cohen-Kettenis et al., 2003; de Vries et al., 2016; Levitan et al., 2019; Steensma et al., 2014). Considering that gender nonconforming behavior is often evaluated negatively by peers, children with a GD diagnosis often experience a lack of social support from their peers or PPR, which in turn is associated with poorer psychological functioning. Family support or good general family functioning (GFF) levels on the contrary, may act as a protective factor against such health risks in youth with a GD diagnosis (Levitan et al., 2019; Simons et al., 2013). For example, in a population of 66 American adolescent transgender youth, parental support was significantly associated with higher life satisfaction, lower perceived burden related to being transgender and fewer depressive symptoms (Simons et al., 2013).

And the authors specifically note that this sample largely consisted of children who were strongly supported by their families, and these results may not be applicable to children whose gender identity is not supported:

Caution is also warranted in generalizing the results to all children with a GD because of the small and relative unique sample. All 54 children in the analysis sample were referred to the clinic for their GD, most of them came from families with a medium or high socio-economic background and the family support of the children’s gender identity was generally high. Due to the health care situation in Germany for children and adolescents with a GD diagnosis, some families go to considerable length to get access to treatment which they probably would not do if they did not generally support their child’s personal situation. At the same time, the clinical guidelines of the Hamburg GIS are quite liberal and allow for individual treatment pathways. Thus, these findings might not apply to a more diverse sample of transgender children who are not supported in their gender identity or expression by parents or clinicians, or children who identify themselves on a broader gender spectrum.

Nothing in this source cited by the FLDOH supports the position that social transition should be withheld from children or adolescents. Rather, the authors conclude that families, peers, and communities should support gender-dysphoric youth as their development unfolds:

Interventions targeted at reducing stigmatization among children and adolescents in the general population and at schools are essential, since children with a GD diagnosis often lack peer support (Cohen-Kettenis et al., 2003; Steensma et al., 2014) and transgender adolescents are more likely to be bullied at school (Toomey et al., 2010). Both peers and family should be incorporated in the psychosocial treatment of this population as early as possible, because incorporating parents’ needs and feelings in the psychotherapeutic process could improve the child’s situation as well. Parents themselves can be affected by their child’s GD and may experience parenting stress (Kolbuck et al., 2019).

Although claims that gender affirmation through transitioning socially is beneficial during this early stage could not be supported from the present results, supporting this step may still be considered in individual cases and together with the whole family. A clinical approach that considers children to explore their identity without strict criteria, but with an open mind, may allow for a discussion of all possible outcomes and individual strategies of exploring gender identity during childhood.

The FLDOH’s source thoroughly contradicts the FLDOH’s own guidance against social transition, puberty blockers or hormone therapy for anyone under 18; instead, all of these are recognized as important options that should be available to trans youth.

Chew et al. (2018) say puberty blockers work and withholding them is unethical

Citing Chew et al. (2018), FLDOH writes:

One review concludes that “hormonal treatments for transgender adolescents can achieve their intended physical effects, but evidence regarding their psychosocial and cognitive impact is generally lacking.”

However, this quotation from Chew et al. was referring to evidence regarding the psychosocial and cognitive impact of hormone therapy specifically – not puberty blockers. The authors went on to conclude that puberty blockers have positive physical and psychosocial effects, and hormone therapy has positive physical effects:

GnRHas successfully suppressed endogenous puberty, consistent with the primary objective of this treatment, although there was only a single study in which researchers actually recorded these data. GnRHas were observed to be associated with significant improvements in global functioning, depression, and overall behavioral and/or emotional problems but had no significant effect on symptoms of GD. The latter is probably not surprising, because GnRHas cannot be expected to lessen the dislike of existing physical sex characteristics associated with an individual’s birth-assigned sex nor satisfy their desire for the physical sex characteristics of their preferred gender. Like GnRHas, the antiandrogen cyproterone acetate effectively suppressed testosterone in transfemale adolescents, but its potential psychosocial benefits remain unclear. Meanwhile, GAHs increased estrogen and testosterone levels and thus induced feminization and masculinization, respectively, of secondary sex characteristics. However, in the case of breast development, the outcomes were subjectively less in size than expected in the majority of recipients, and the potential psychosocial benefits of GAHs remain unknown.

They recommend additional studies with larger sample sizes and tracking of more outcome measures:

Large, prospective longitudinal studies, such as have been recently initiated, with sufficient follow-up time and statistical power and the inclusion of well-matched controls will be important, as will the inclusion of outcome measures that investigate beyond the physical manifestations.

Of note, this source highlights the challenges of conducting randomized controlled trials of puberty blockers and hormone therapy given that withholding this care is unethical:

In this regard, although randomized controlled trials are often considered gold standard evidence for judging clinical interventions, it should be noted that, in the context of GD in which current guidelines highlight the important role of hormonal treatments, conducting such trials would raise significant ethical and feasibility concerns.

The FLDOH has not provided accurate context for its quote, and this source also does not support the FLDOH’s recommendation that puberty blockers or hormone therapy should be withheld from those under 18.

Carmichael et al. (2021) present limited and ambiguous data on puberty blockers

The FLDOH asserts:

Anyone under 18 should not be prescribed puberty blockers or hormone therapy.

Carmichael et al. (2021) is cited in supported of this statement. This study reports a null result for improvement in measured psychological functioning or quality of life (no change) in 44 youth aged 12-15 during the time they were treated with only puberty blockers (median 31 months, range 12-59) and prior to hormone therapy. Because of the limitation that there was no control group from whom puberty blockers were withheld, this study does not provide sufficient information to distinguish between a number of possibilities. One is that puberty blockers alone actually may not improve psychological functioning in this group; another is that puberty blockers did prevent an expected decline in psychological functioning over this time that typically seen among cis youth in this age range. The authors discuss these possibilities:

Psychological distress and self-harm are known to increase across early adolescence. Normative data show rising YSR total problems scores with age from age 11 to 16 years in nonclinical samples from a range of countries. Self-harm rates in the general population in the UK and elsewhere increase markedly with age from early to mid-adolescence, being very low in 10 year olds and peaking around age 16–17 years. Our finding that psychological function and self-harm did not change significantly during the study is consistent with two main alternative explanations. The first is that there was no change, and that GnRHa treatment brought no measurable benefit nor harm to psychological function in these young people with GD. This is consonant with the action of GnRHa, which only stops further pubertal development and does not change the body to be more congruent with a young person’s gender identity. The second possibility is that the lack of change in an outcome that normally worsens in early adolescence may reflect a beneficial change in trajectory for that outcome, i.e. that GnRHa treatment reduced this normative worsening of problems. In the absence of a control group, we cannot distinguish between these possibilities.

They further point out that distressing symptoms related to gender dysphoria and body image may not be alleviated by puberty blockers alone – instead, puberty blockers simply prevent the gender-incongruent development of natal puberty, while the gender-congruent development accompanying cross-sex hormone therapy does reliably produce positive changes:

Gender dysphoria and body image changed little across the study. This is consistent with some previous reports and was anticipated, given that GnRHa does not change the body in the desired direction, but only temporarily prevents further masculinization or feminization. Other studies suggest that changes in body image or satisfaction in GD are largely confined to gender affirming treatments such as cross-sex hormones or surgery.

Additionally, these youth reported that their experience of puberty blockers during this time was broadly positive and that they wished to continue treatment:

Young people’s reports of change in family and peer relationships were predominantly positive or neutral at both time points. Positive changes included feeling closer to the family, feeling more accepted and having fewer arguments. Those reporting both positive and negative change reported feeling closer to some family members but not others. At 6–15 months, negative family changes were largely from family members not accepting their trans status or having more arguments. But by 15–24 months only one young person reported this. Improved relationships with peers related to feeling more sociable or confident and widening their circle of friends; negative changes related to bullying or disagreements at school. Again, at 15–24 months only one young person reported negative change, related to feelings of not trusting friends.

At 6–15 months, changes in gender role were reported by 66% as positive, including feeling more feminine/masculine, living in their preferred gender identity in more (or all) areas of life and feeling more secure in their gender identity, with no negative change reported. At 15–24 months, most reported no change although 41% reported positive changes including experimenting more with physical appearance and changing their details on legal documents.

All young people affirmed at each interview that they wished to continue with GnRHa treatment. Note that this was also the case when asked routinely at medical clinics (excepting those who briefly ceased GnRHa as noted above).

The strongest interpretation of Carmichael et al. is that this is one neutral finding of neither harms nor benefits within the period of treatment with puberty blockers alone, among a body of mixed evidence with other studies also reporting clearly positive results during this treatment; Carmichael et al. also did not examine outcomes from later hormone therapy in this group. At no point do the authors find any cause for withholding all treatment with puberty blockers or hormone therapy before age 18 as the FLDOH recommends. Instead, as with several other studies cited by the FLDOH, this is a call for further research of trans youth receiving such treatments, with the intention of better informing their clinical care and resolving the uncertainties raised by the addition of this inconsistent finding to the literature. FLDOH’s use of this study implies that in a setting of uncertainty, they wish to withhold from trans youth a treatment that may be preventing further harm to them.

Goddings et al. (2014) does not address trans youth or use of puberty blockers

In claiming puberty blockers and hormone therapy should be withheld from anyone under 18, the FLDOH cites Goddings et al. (2014), “The influence of puberty on subcortical brain development”. This is a study of a series of brain MRIs of 275 presumably cisgender participants from ages 7-20 to track the changes of typical development during puberty; this was not a study of transgender youth and did not involve any use of puberty blockers or hormone therapy. FLDOH says of this study in its “Fact Check” press release:

According to a study in NeuroImage, “pubertal development was significantly related to structural volume in all six regions [in brain regions of interest] in both sexes,” meaning that the process of puberty is important to brain development.

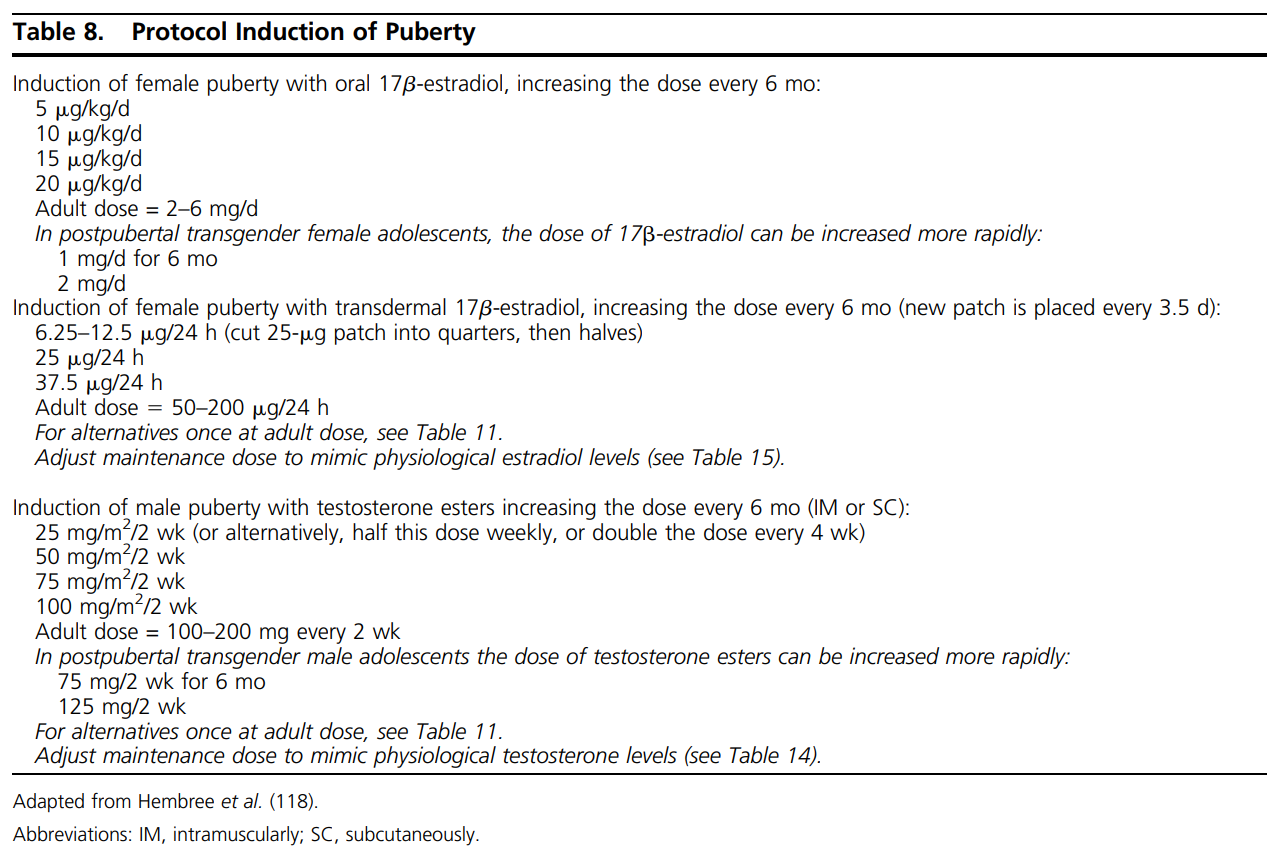

The process of puberty being important to brain development does not argue for or against the use of puberty blockers or hormone therapy in trans youth under 18. These youth do not remain on puberty blockers indefinitely or avoid experiencing puberty altogether – the puberty of their identified sex is induced with cross-sex hormone therapy, the next stage of treatment following puberty blockers. The Endocrine Society’s treatment guidelines describe such a protocol for puberty induction in trans youth (Hembree et al., 2017):

Again, Goddings et al. did not examine the brain development of trans adolescents during treatment with puberty blockers or hormone therapy, and this source does not provide any apparent support for the position that “Anyone under 18 should not be prescribed puberty blockers or hormone therapy.”

Haupt et al. (2020) is largely about adult trans women, not use of puberty blockers

FLDOH also cites the Cochrane review “Antiandrogen or estradiol treatment or both during hormone therapy in transitioning transgender women” (Haupt et al., 2020), which encompassed only hormone therapy for trans women aged 16 and over, not the use of puberty blockers in adolescents:

We aimed to include randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-RCTs, and cohort studies that enrolled transgender women, age 16 years and over, in transition from male to female. Eligible studies investigated antiandrogen and estradiol hormone therapies alone or in combination, in comparison to another form of the active intervention, or placebo control.

However, these criteria ended up encompassing no studies, with the authors concluding that under these terms they couldn’t say anything about the question either way:

As no studies met the inclusion criteria, we were unable to calculate any effects of the interventions.

By citing this source, the FLDOH is claiming that puberty blockers and hormone therapy should be withheld from anyone under 18 on the basis of a publication that wasn’t about puberty blockers or trans youth and did not provide any information about the outcomes of any gender-affirming care.

Kaltiala et al. (2020) studied adolescents and young adults who transitioned too late for puberty blockers

FLDOH cites Kaltiala et al. (2020) in its position that puberty blockers and hormone therapy should be unavailable to anyone under 18. However, Kaltiala et al. note that these youth were first diagnosed at a average age of 18.1 years (range 15.2-19.9) and all presented once the window for use of puberty blockers had passed, meaning all had experienced a gender-incongruent natal puberty. The authors cite this as a likely reason for the lack of change seen in the proportion showing good psychological functioning before and after treatment with hormone therapy:

What is more, even if the majority also functioned well in the domains studied during the first year on cross-sex hormones, no statistically significant improvements in functioning were observed in the group as a whole, and in the domain of peer relationships the share of those with normative contacts decreased. This is in disagreement with earlier studies suggesting improved functioning and reduced psychiatric symptoms in adolescent onset hormonal treatment of gender dysphoria, and likely due to older age, more difficult psychopathology and different intervention (cross-sex hormones vs. GnRH analogues) in our sample. Our subjects were all post-pubertal and halting of development was thus not possible.

Even so, this study found a significant decrease in trans youth’s need for treatment for depression, anxiety, and self-harm/suicidality at a one-year followup:

Need for treatment due to depression, anxiety and suicidality/ self-harm was recorded less frequently during the real-life phase than before it. This is in line with the conclusion of a relatively recent meta-analysis that in adults with gender dysphoria, cross-sex hormonal treatment alleviates anxiety, and may also reduce depression or depressive symptoms. However, need for psychiatric treatment overall did not decrease from the level before and during the gender identity assessment to the real-life phase. New needs had also emerged about as frequently as need for treatment diminished. . . . Depression, anxiety and suicidality/self-harm are often assumed to be secondary to gender dysphoria, and our findings may be interpreted as lending some support to that assumption among adolescents, similarly as earlier research seems to imply for adults.

The authors call for more comprehensive support for these youth in all aspects of their psychosocial health beyond addressing only gender dysphoria:

If the adolescents diagnosed with transsexualism had had difficulties at school/work as during the gender identity assessment, they mainly continued to have difficulties during the real-life phase. Only a minority moved from progressing with difficulties to progressing normatively, and equally many deteriorated during follow-up. Improved functioning as a consequence of alleviating gender dysphoria and passing better in the desired role is commonly assumed but has not previously been researched in relation to education/work. Our findings suggest that treatment of gender dysphoria does not suffice to improve functioning in education and working life. Difficulties in school adjustment and learning are common among gender-referred adolescents and often not properly addressed, on the assumption that treatment of gender dysphoria would relieve an array of problems. Educational difficulties need to be fully addressed during adolescence regardless of gender identity. . . . An adolescent’s gender identity concerns must not become a reason for failure to address all her/his other relevant problems in the usual way.

Notably, they do not call for gender dysphoria to go unaddressed by withholding puberty blockers or hormone therapy from this group. The FLDOH has cited a study of less than optimal improvements among youth who largely could not access puberty blockers or hormone therapy until after turning 18, and then declared on this basis that these youth should not be able to access puberty blockers or hormone therapy before turning 18. The FLDOH’s position is unsupported by this study or by the other studies cited, which most often reach the very opposite conclusion. Sloppy illusion and sleight-of-hand that falter under the gentlest examination are a completely unacceptable basis for policy or recommendations. The Florida Department of Health has failed the trans youth of Florida with this cruel joke of “guidance” from an unreliable guide. ■

Gender Analysis is run by two gay moms who are busy with work, school, and home in between slaying anti-trans misinformation. Your support on Patreon helps us keep up the fight!