< Previously: Dr. Stephen Levine and the Plot to Police America’s Gender, part 1.

How Steensma et al. can’t support Levine’s claim that social transition causes persistence.

Persistent gender dysphoria into adolescence is not rare, including in Steensma et al.

Persistent gender dysphoria into adolescence is not rare, including in Steensma et al.

Steensma et al. (2013) is the only source of any clinical evidence that is cited in support of Levine’s claim – that allowing social transition in childhood is an action that directly causes a greater likelihood of persistence of gender dysphoria in an individual than if they had not socially transitioned. Do the findings of Steensma et al. reflect Levine’s model of this supposed influence on child gender identity development? Largely, no. The authors report a limited model involving multiple factors that remain uncertain in their predictive value, let alone their causal influence or the possibility of actual intervention. It is the very opposite of the model of certain causation Levine describes in his testimony on these findings.

The study “Factors Associated With Desistence and Persistence of Childhood Gender Dysphoria: A Quantitative Follow-Up Study” (“Persisting Childhood Gender Dysphoria”) followed 79 assigned-male and 48 assigned-female youth from their initial referral to Amsterdam’s VUmc child gender clinic before puberty and through adolescence, tracking whether their gender dysphoria persisted into puberty or desisted (with desistance assumed if they stopped going to this clinic, a known limitation of this study that has been covered elsewhere). The authors aimed to identify any differences in the persisting and desisting populations and the extent to which these differences might be associated with a greater likelihood of persistence:

The present study examined possible factors associated with persistence of childhood GD by comparing a number of childhood variables (e.g., demographic background, GD, gender-variant behavior, psychological functioning, and quality of peer relations) between adolescent persisters and desisters who were clinically referred to our gender identity service in childhood. In addition to this, we examined psychosexual outcomes, body image, and the intensity of GD at the time of follow-up in adolescence.

Followup studies of childhood gender dysphoria into adolescence have been frequently misused to claim, as the Florida Department of Health did in April, that 80% or more of trans or gender-dysphoric children will go on to identify as cis and experience resolution of their dysphoria in adolescence. The implication is typically that recognition and affirmation of an apparently trans child’s gender would therefore be mistargeted, premature, and mistaken. Studies like these, however, show very clearly that the authors did not intend to treat gender-dysphoric children as a single group of whom some proportion will continue experiencing dysphoria in adolescence and some other proportion will not.

By looking at any differences in traits associated with continuation or discontinuation of dysphoria, researchers aim to identify features respectively linked to two groups: one that is very likely to continue experiencing gender dysphoria into adolescence, and one that is unlikely to experience this. Aggregating those populations into one group, using a single combined figure to describe the collective “desistance” rate of all of them, means disregarding the intentions and the findings of the very studies typically cited to support this misleading claim.

Levine makes a similar error in describing the findings of Steensma et al. in his testimony. In B.P.J. v. West Virginia as in his other testimony, he describes continuation of childhood gender dysphoria into adolescence as an anomalous outcome:

113. A distinctive and critical characteristic of juvenile gender dysphoria is that multiple studies from separate groups and at different times have reported that in the large majority of patients, absent a substantial intervention such as social transition or puberty blocking hormone therapy, it does not persist through puberty.

114. A recent article reviewed all existing follow-up studies that the author could identify of children diagnosed with gender dysphoria (11 studies), and reported that “every follow-up study of GD children, without exception, found the same thing: By puberty, the majority of GD children ceased to want to transition.” (Cantor 2019 at 1.)

Combined “desistance” rates are an unreliable and misleading figure because they collapse multiple distinct groups into one; even so, samples of youth in similar studies have shown rates of discontinuation of dysphoria at adolescence ranging from over 80% to below 50% (Temple Newhook et al., 2018). Treating even a single trans child’s identity as too marginal to matter is unacceptable; refusing to affirm a trans child’s gender based on the presumption that they’ll later “desist” can still harm them in the present. Levine would casually dismiss half of them or more – Steensma et al. (2013) included 47 trans adolescents with continuing dysphoria – with his sweeping generalization that trans children’s gender and dysphoria simply “does not persist through puberty”.

Levine’s disregard for the large numbers of trans children who do become trans adults functions to frame “desistance” as the default trajectory of trans children, with persisting dysphoria an exception, allegedly only caused by “a substantial intervention such as social transition or puberty blocking hormone therapy”. Recognizing that persistence is simply common at baseline would undermine his argument that it must be an unusual case with specific, modifiable causes.

Levine lacks domain knowledge in statistics and misunderstands “unique predictors” in multiple regression

To support his argument that persistence of childhood gender dysphoria is rare and caused by a modifiable factor, social transition in childhood, Levine appears to misread key portions of Steensma et al.’s methodology and statistical analysis. Merely reading the abstract makes clear that this is a study including several factors associated with persistence rather than only one, it is a study of associations rather than causative mechanisms, and it is not exclusively focused on potentially modifiable factors such as social transition status:

We found a link between the intensity of GD in childhood and persistence of GD, as well as a higher probability of persistence among natal girls. Psychological functioning and the quality of peer relations did not predict the persistence of childhood GD. Formerly nonsignificant (age at childhood assessment) and unstudied factors (a cognitive and/or affective cross-gender identification and a social role transition) were associated with the persistence of childhood GD, and varied among natal boys and girls. Conclusion: Intensity of early GD appears to be an important predictor of persistence of GD.

As described in the abstract, Steensma et al. primarily found that the intensity of a child’s gender dysphoria is positively associated with the likelihood of persistence: the more strongly a child in this sample experienced gender dysphoria, the more likely it is for them to continue being dysphoric into adolescence. This is not a study about social transition as a causative factor – it is about social transition as one of many factors that are indicative of the intensity of a child’s gender dysphoria.

The authors immediately cite several previous findings in this area and the factors that were found to be associated with persistence of childhood gender dysphoria, including “complete childhood GID diagnosis”, “more gender-variant behavior”, “a higher intensity of GD in childhood”, “more gender-variant behavior and a higher intensity of GD in childhood”, “more gender-variant behavior and GD during childhood”, and “the intensity of childhood GD”:

Knowledge of the factors associated with persistence of childhood GD is limited. Prospectively, 1 study by Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis, reporting on the outcome in adolescence and early adulthood for 77 clinically referred children with GD (21 persisters and 56 desisters), found that the percentage of a complete childhood GID diagnosis was higher for children with persisting GD than for children with desisting GD. Furthermore, compared to the desisters, the persisters showed more gender-variant behavior and a higher intensity of GD in childhood. In line with these findings, Drummond et al. showed that girls with persisting GD recalled significantly more gender-variant behavior and GD during childhood than the girls classified as having desisting GD. More recently, another study by Singh in 139 natal boys with GD confirmed the link between the intensity of childhood GD and adolescent and adult persistence of GD.

Again, these studies did not focus on whether or not a trans or gender-questioning child is permitted to socially transition or the supposed effects of socially transitioning on the likelihood of persistence. These were studies of how strongly these children experienced symptoms of gender dysphoria and exhibited this in their behaviors, and this was consistently linked to the likelihood that a gender-dysphoric child will become a gender-dysphoric adult. The authors also review their earlier study (Steensma et al., 2011) of the qualitative experiences of youth whose gender dysphoria either persisted into adolescence or desisted, including key differences such as “persisters explicitly indicated that they believed that they were the ‘other’ sex” and “the persisters indicated that their discomfort originated from the experience of incongruence between their bodies and their gender identity”:

Indications of more subtle childhood differences between persisters and desisters were reported in a qualitative follow-up study of 25 children with GD (14 persisters and 11 desisters) by Steensma et al. They found that both the persisters and desisters reported cross-gender identification from childhood, but their underlying motives appeared to be different. The persisters explicitly indicated that they believed that they were the “other” sex. The desisters, however, indicated that they identified as girlish-boys or boyish-girls who only wished they were the “other” sex. With regard to the reported bodily discomfort by the persisters as well as by the desisters, the persisters indicated that their discomfort originated from the experience of incongruence between their bodies and their gender identity, whereas the desisters indicated that the discomfort was more likely to be a result of the wish for another body to fulfill the desired social gender role. As the information was based on subjective recollection and was therefore susceptible to biased recall, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Taken together, the prior research suggests that persistence of childhood GD is most closely linked to the intensity of the GD in childhood, the amount of gender-variant behavior, and possible differences in motives or cognitive constructions of the dysphoria.

The prior body of research consistently shows that youth with more intense gender dysphoria are more likely to have persisting gender dysphoria into adolescence. Did the present study find that socially transitioning can also cause a greater likelihood of persistence? No – this study found that under one possible statistical model chosen by the authors to describe this sample, social transition status explained 12% of the outcome of persistence or desistance in one group and explained 0% of this outcome in another group.

The statistical models presented by the authors are intended to describe relationships between several measures of gender incongruence and the binary outcome of persistence or desistance. In this study, a child could be marked as “socially transitioned” even if, for example, an assigned-male child still used a boy’s name and he/him pronouns:

The diagnosis, made by either a child psychologist or psychiatrist, was categorized as follows: children who met all criteria for a DSM-IV-TR GID diagnosis, or children who did not meet all criteria and were subthreshold for a GID diagnosis. Social role transition was determined through 2 questions by 1 of the parents around the time of referral. Parents indicated whether their child had socially transitioned to the preferred gender role on a 3-point scale; no; yes, but not in all situations; or yes, completely. In an open question, they could give further information on hairstyle, clothing, and in which pronoun and name the child was addressed. Based on this information, the children were categorized as follows: no social transition; partial transition (transition in clothing style and hairstyle, but without a change of name and pronoun change); complete transition (transition in clothing and hairstyle; change of name and use of pronoun). Because of the unequal distribution over the 3 categories for boys and girls (Table 1), the 3-point scale was recoded into a dichotomous scale in which 0 indicated no transitioning (category 1) and 1 indicated some transitioning (categories 2 and 3).

It’s crucial to understand that these are the concrete details of Levine’s hypothesis that a social transition in childhood is causative of a greater likelihood of persistence. Even while calling a boy by he/him and his given name, a change of haircut or attire would, in Levine’s telling, constitute some form of “medical treatment” that will significantly alter a child’s internal sense of gender identification and the eventual trajectory of their gender dysphoria.

Other measures of gender variance used in the present study are inventories of gender dysphoria and gender-atypical behavior:

The Dutch version of the Gender Identity Interview for Children (GIIC) is a 12-item child informant instrument that measures 2 factors: “cognitive gender confusion” and “affective gender confusion.” Cognitive gender confusion is assessed by 4 questions asking whether the child identifies as a boy or a girl, Affective gender confusion is assessed by means of 8 questions focusing on affective aspects of gender identity (e.g., “Are there any things that you don’t like about being a boy?”). Higher scores on the GIIC reflect more gender-atypical responses. The Dutch version of the Gender Identity Questionnaire (GIQ) is a 14-item parent-report questionnaire representing 1 factor. The focus of items is on gender-variant behaviors, with higher scores coded in this study to represent a greater frequency of gender-variant behaviors.

The GIIC (Wallien et al., 2009) and the GIQ (Cohen-Kettenis et al., 2006) include a number of questions about gender incongruence that are unrelated to social transition status: things they don’t like about being their assigned sex, whether they think it’s better to be a boy or a girl, whether (for AMABs) they want to be a girl, whether they feel more like a girl than a boy, whether they see themselves as a boy or a girl in their dreams, whether they think they are really a girl, “states the wish to be a girl or woman”, “states that he is a girl or a woman”, and “talks about not liking his sexual anatomy”.

These are aspects of gender variance that exist whether they are expressed or not, or whether their expression is permitted or not; they are not a potentially modifiable factor or an “intervention” in the sense that Levine considers permitting social transition to be an “intervention”. Likelihood of persistence was found to be predicted largely by responses to these inventories – not caused by responses to these inventories.

The authors explain their process for building this statistical model:

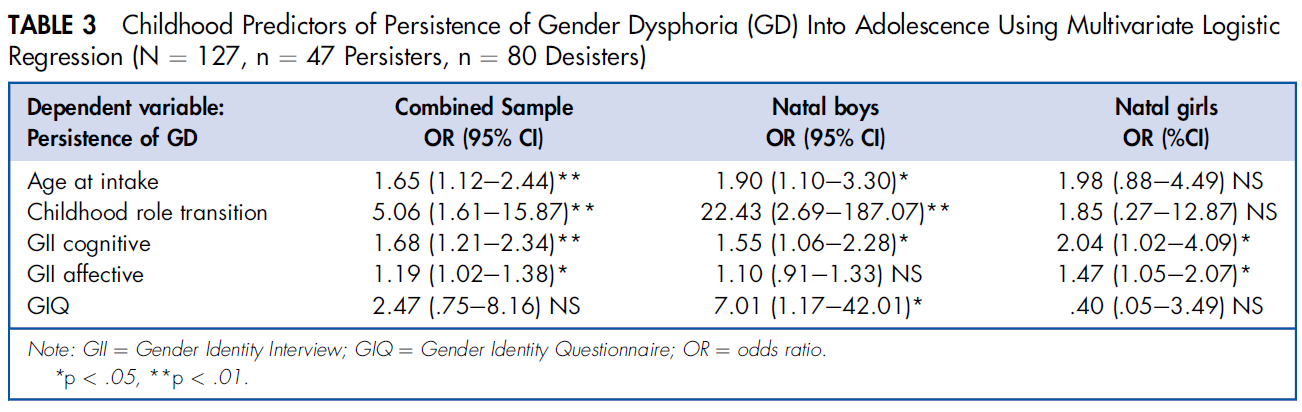

To examine the simultaneous contribution of multiple factors, multivariate logistic regressions were run for the combined sample and separately by natal sex. Variables were retained in the model based on their unique contribution to explaining persistence of GD. Variables with very high correlations with other GD measures (e.g., whether or not a diagnosis was given) were not useful for the multivariate model and thus were dropped (Table 3).

This appears to be where Levine has misunderstood the meaning of “unique contribution”. He has interpreted “unique” in the lay sense, believing this means social transition holds some singular status as perhaps the only predictor – and only cause – of persistent gender dysphoria. However, “unique contribution” has a specific meaning in the context of statistical models like these. The authors are contrasting this model incorporating multiple variables with simpler models incorporating only one variable:

Bivariate logistic regressions estimated the individual contribution of the childhood variables to examine which variables predicted persistence of GD (Table 2). Age and natal sex were the only significant demographic predictors. Older children and girls were more likely to be persisters than younger children and boys. Gender relevant items from the CBCL and TRF, social role transition, responses to the GIIC and GIQ, and receipt of a GID diagnosis in childhood were all significant indicators of adolescent persistence of GD.

These simpler bivariate (two-variable; one predictor and one outcome) models found a number of individually significant associations. But because each of these models only takes into account a single variable such as a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, they fail to incorporate the rest of the variables, and they do not control for the effect of other variables. This is the reason it was necessary for the authors to make a “multivariate” (multiple variables; many predictors and one outcome) model that does take this into account. When they did, they found that some variables were no longer significant and could be left out, while some variables remained significant and should be included. These remaining significant variables were included because of that “unique contribution”.

(Disclaimer: I am a statistics major and multivariate logistic regression models like these were an entire unit of Statistical Methods III as well as my final project, on which I got an A. I am trained in this and I know what I’m doing. Please read chapter 22, “Logistic Regression Analysis”, in Kleinbaum et al.’s “Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods”.)

A number of these unique contributors remained, including many more than social transition status – and social transition status was itself not always significant:

Among those assigned female, social transition was not found to be a useful predictor of persistence of gender dysphoria at all – only their responses to two subscales of the GIIC remained significant. And in those assigned male, social transition was found to be significant, but so were non-modifiable factors such as their age, their response to a subscale of the GIIC, and their parents’ responses on the GIQ.

Crucially, while a given variable may be found to be a statistically significant predictor, that does not necessarily mean the actual magnitude of its contribution is large. The authors describe their model for those assigned male as accounting for 62% of the eventual outcome of persistence or desistance, meaning 38% of “why” a child’s gender dysphoria persists or desists remains unexplained by the model:

Among natal males, 62% of the variability in the persistence of GD was accounted for by age at intake, social role transition, the cognitive subscale of the GIIC, and the total score of the GIQ. Once these variables were accounted for, responses to the affective component of the GIIC did not predict additional variance in persistence. Social role transition accounted for the largest portion of unique variability (12%), whereas each of the other significant predictors accounted for 6% to 7% of unique variability in persistence of GD.

Once more, this means that under the authors’ model, social transition explained 12% of whether an assigned-male child’s dysphoria would persist into adolescence. This study does not establish social transition or any other factor here as causing persistence, only associated with it in this limited sense. Even if we were to accept this model as somehow being definitive rather than a provisional and approximate description of some underlying data-generating process, the 12% contribution of social transition is dwarfed by the overall contributions of other non-modifiable factors, including these children’s experiences of symptoms of gender dysphoria and their parents’ responses to inventories of gender-variant behaviors. And for those assigned female, only their own responses to the GIIC were found to be significant predictors of persistence, with social transition playing no role at all:

For natal females, 62% of the variability in the persistence of GD was accounted for by cognitive and affective responses to the GIIC. Once these variables were entered, none of the other predictors contributed unique variance to persistence. Cognitive and affective responses to the GIIC explained 15% each of the unique variability in persistence of GD.

So: Under the models in Steensma et al., persistence of childhood gender dysphoria into adolescence is 88-100% explained by something other than social transition status. Contrast this with Levine’s sweeping assertion in B.P.J. v. West Virginia (p. 37):

Social transition of juveniles, for instance, strongly influences gender identity outcomes to such an extent that it has been described a “unique predictor of persistence.”

Does social transition “strongly influence gender identity outcomes” based on a study which found that persistence into adolescence was 88-100% associated with things that aren’t social transition? No, and Stephen Levine is wrong to cite Steensma et al. as supporting this claim.

Later studies do not support Levine’s hypothesis that social transition causes persistence of gender dysphoria

Steensma et al. (2013) offered an exploratory analysis of the data to show possible associations and connections between experiences of gender incongruence in childhood and persistence of gender dysphoria into adolescence, without asserting a causal influence of the kind Levine is proposing. The authors raise the possibility of causation by social transition as an open question for future studies, not as a conclusion of the present study:

Social transitions were associated with more intense GD in childhood, but have never been independently studied regarding the possible impact of the social transition itself on cognitive representation of gender identity or persistence. As we previously indicated, the percentage of transitioned children is increasing and seems to exceed the percentages known from prior literature for the persistence of GD, which could result in a larger proportion of children who have to change back to their original gender role, because of desisting GD, accompanied with a possible struggle; or it may, with the hypothesized link between social transitioning and the cognitive representation of the self, influence the future rates of persistence. Future prospective follow-up studies on children with GD, where cognitive markers and specific indicators of social transitioning are incorporated, may shed more light on this question.

Rae et al. (2019) examined this question with a study designed to determine whether socially transitioning would increase the intensity of cross-gender identification in gender-questioning children compared to those who had not socially transitioned. As found in Steensma et al., intensity of gender dysphoria and gender variance was associated with likelihood of persistence of gender dysphoria into adolescence, and if social transition in children were associated with an increase in gender congruence, it could mean that social transition leads to persistence. Rae et al. explicitly raise this possibility:

As a second research question, we also investigated whether social transitions are associated with changes in the degree to which children express their gender identity and preferences. That is, would an assigned male who is living as a girl (i.e., a transgender girl) be more feminine than an assigned male who has not yet transitioned but later does? On the one hand, after a transition, a child is more likely to be treated as a member of his or her identified gender in everyday interactions because the child now appears (e.g., through clothing or pronouns) to be a member of that gender group. This treatment may reinforce the child’s sense of identity, thereby leading to more extreme preferences and identity expression. In this case, a child tested before transitioning might not show preferences and identity expression to the same extreme as a child who has already transitioned.

Instead, they found the opposite: cross-gender identification did not intensify in children who socially transitioned, and those who would later socially transition already exhibited these high levels of cross-gender identification before socially transitioning.

Children who went on to socially transition showed gender identification and preferences comparable in magnitude with those of children who had already transitioned (i.e., transgender participants) and children whose assigned sex and gender identity had aligned for their entire life (i.e., control participants). Stated differently, an assigned male who will later transition to live as a girl is roughly as feminine before transition as a transgender girl is after a transition, and both are comparable in degree of feminine identity and preferences to a non-transgender girl. Again, this effect was remarkably robust across different analytic and data-processing decisions. Although replication of this effect is needed, preferably from a longitudinal study comparing a single group of children before and after transition, this finding could reduce worries that the transition itself is leading children to identify as, or behave in ways more stereotypically associated with, the opposite assigned sex.

Here, social transition has been temporally excluded as a cause of intense cross-gender identification – this intensity of gender incongruence, which is known to be associated with gender dysphoria continuing into adolescence, is already present before social transition. This weighs heavily against Levine’s claim that permitting social transition, or withholding social transition, constitutes an “intervention” that has any effect on eventual persistence of gender dysphoria. Contrast this with Levine’s assertion in Tingley v. Ferguson (p. 29):

Social transition of young children is a powerful psychotherapeutic intervention that changes outcomes. In contrast, there is now data that suggests that a therapy that encourages social transition before or during puberty dramatically changes outcomes.

Rae et al. have examined the question raised in Steensma et al. (2013) and found no evidence of this proposed mechanism, yet Stephen Levine continues to claim in expert affidavits that a large body of clinical experience and data says otherwise.

Coming up: Stephen Levine has made misrepresentations about transgender healthcare in previous cases. A growing number of right-wing advocacy groups are now popularizing his incorrect argument against social transition.